The present moment is a good time to ask questions about what a civic-oriented design curriculum should look like. From Moholy Nagy to Papenek, these questions have been posed before, and their penetrating nature has created fissures in inhospitable ground. These fissures, in turn, have created today’s fertile environment, where socially-minded design educators are sowing seeds of their own. As a means of furthering these explorations, gatherings of design educators have been convening under the auspices of initiatives such as DESIS (Design for Sustainability and Social Change), LEAP Symposium, and the Winterhouse Symposium for Design Education and Social Change.

An Exciting New Era of Good Questions

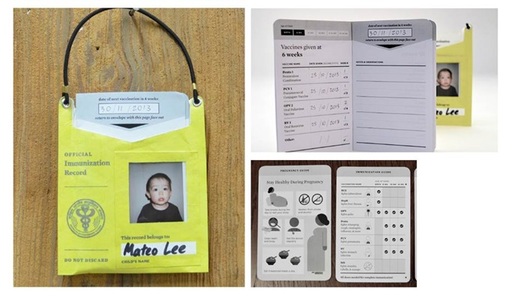

More and more colleges and universities are asking questions about the nature and shape of a civic-oriented design curriculum through the development of classes, symposia and newly launched design degrees. My institution, the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), has been one of those institutions, and some of the results are embodied in a master’s degree called Design for Sustainability, which launched in 2009. The program is built on a triple-bottom line pursuit of wellbeing through a three-pronged approach to innovation (see figure above).

Through systems thinking and design strategy lenses, students are exposed to technical innovations leading us into the 21st century; social innovations of participatory design and its ilk; and perceptual innovations of behavior change and meaningful user experience. That exposure is then put to the test among interdisciplinary teams in real world situations; some with singular clients that range from corporations to community groups; and some that engage a complex mix of stakeholders with competing motivations.

Pluck One String: A Mantra is Not a Tool

Asking the right questions about the intent and efficacy of design education has led to challenging students to ask the right questions about the nature and placement of their design efforts. Yet, the inevitable decision to select the ‘most appropriate’ choice when it comes to scope can be fraught with uncertainty.

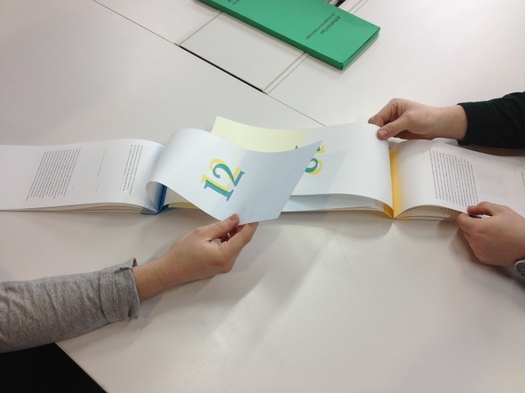

As an aid to working through such matters, and as a complement to contextual research methods, students can be challenged to imagine the complexity of any given social system as an intricate web of connections (see figure above), then encouraged to focus on each intersection as a convergence of processes (conversations, policies, norms, beliefs, etc.). Being confronted with such complexity can instill the necessary humility one needs in such situations; attempts at strumming such a web are laden with hubris, and more potentially harmful than helpful in their clumsy ambition. Conversely, as a means of avoiding paralysis in the face of such daunting landscapes, students can be encouraged to ‘pluck one string.’

A ‘pluck’ acknowledges any proposed design solution as a single intervention along a longer continuum. Focusing on a single string lends an appropriate scope, while at the same time suggests the interconnectivity of all things; with so many overlaps, any single pluck will set other strings humming to one degree or another. In this way the task of defining a scope can be centered on the mindful placement of design interventions within the social milieu. Wendell Berry has proffered a term for such approaches:

solving for pattern.

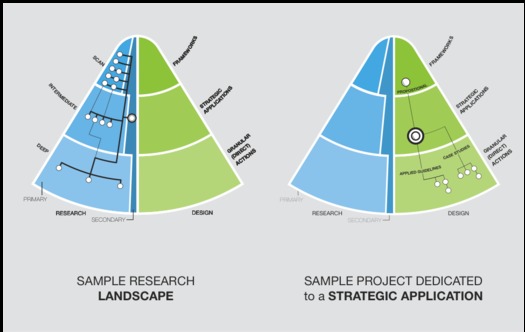

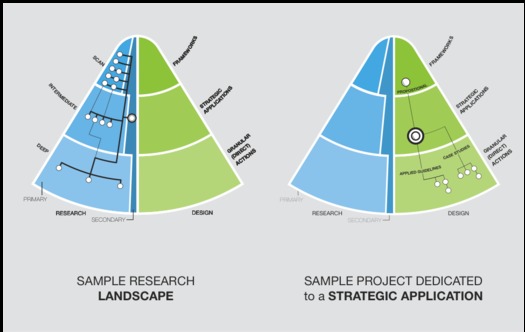

A Systems Sensitive Design Tools as a Means of Questioning Through IntentionsYet setting the tone by providing a big-picture framing like ‘pluck one string’ is only a starting point. A mantra is a good reminder, but it’s no tool. With this fact becoming increasingly evident over the sweep of several academic quarters of teaching systems sensitive thinking, a worksheet was created which helped place proposed design interventions on a landscape of possibility. The tool forces students to visualize the interrelated nature of small actions and broader frameworks. It enables them to visualize the related nature of research and design decisions. And it acts as a reminder of what research directions were not pursued, and what potential design interventions were not executed.

The worksheet has been helpful in nurturing constructive conversations between team members, between teams, and between teams and clients. Discussions resulting from its use have helped facilitate the exploration of the potential ramifications of design decisions. It’s shared here in the spirit of opened-source experimentation: Take it, shake it, break it, remake it.

Scott Boylston is a Professor of Design for Sustainability at the Savannah College of Art and Design and the co-author and Program Coordinator for the Masters in Design for Sustainability. He is president and co-founder of Emergent Structures, the author of three books and the founder of the Design Ethos conference and ‘DO-ference’. He has served on several boards including the State Board of Directors for the US Green Building Council of Georgia.

Scott Boylston is a Professor of Design for Sustainability at the Savannah College of Art and Design and the co-author and Program Coordinator for the Masters in Design for Sustainability. He is president and co-founder of Emergent Structures, the author of three books and the founder of the Design Ethos conference and ‘DO-ference’. He has served on several boards including the State Board of Directors for the US Green Building Council of Georgia.