May 19, 2011

Unearthly Powers: Surrealism and SF

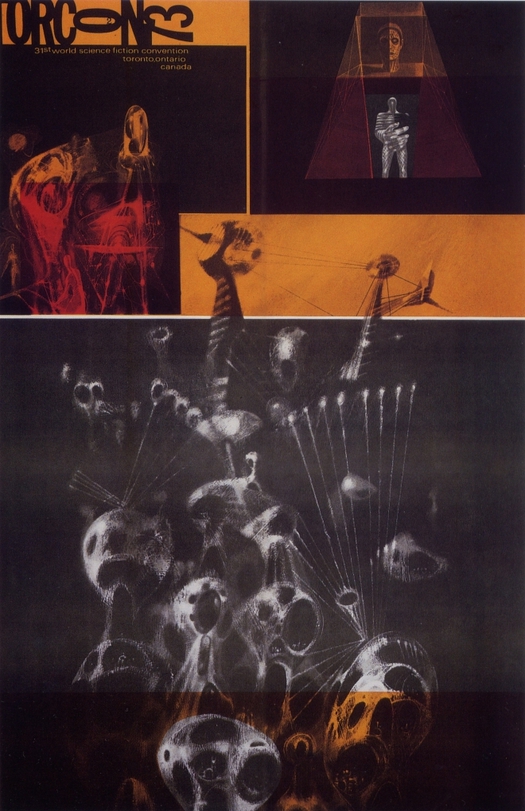

Richard Powers, Torcon 2, poster for the 31st World Science Fiction Convention, 1973

Anyone reading this blog regularly will be aware of my not so secret enthusiasms for Surrealism, science fiction and the writing of J.G. Ballard. A special issue on SF in the Guardian Review last weekend has presented a grab-it-while-you-can opportunity to talk about all three, with particular reference to Richard Powers (1921-96), an artist and illustrator whose work offers perhaps the ultimate fusion of Surrealism and visual SF.

The Guardian asked leading SF writers to choose their favorite novel or author in the genre and tell readers why. For the novelist Christopher Priest, author of The Prestige (later made into a film), it had to be Ballard’s short story “The Voices of Time,” first published in 1960. Here’s what Priest says:

The plot almost defies summary. An imminent global disaster is seen from the viewpoint of a group of sleep-addicted scientists, slowly going mad in a desert installation surrounded by salt lakes, where genetic experiments have bred mutant animals to resist the radiated atmosphere. Meanwhile, a countdown to the end of the universe has begun, a suicidal madman engraves a mandala on the floor of an emptied swimming pool, a sleep-deprived astronomer cruises the dunes in a white Packard saloon, a raven-haired temptress named Coma plays the men off against each other. Somehow it all seems to make crazy and brilliant sense. I have read the story a dozen times, never actually understood it, but also have never failed to draw inspiration and encouragement from Ballard’s pellucid writing and amazing and surreal images.

If that delirious stream of images doesn’t convince you that you need to read Ballard, then nothing will.

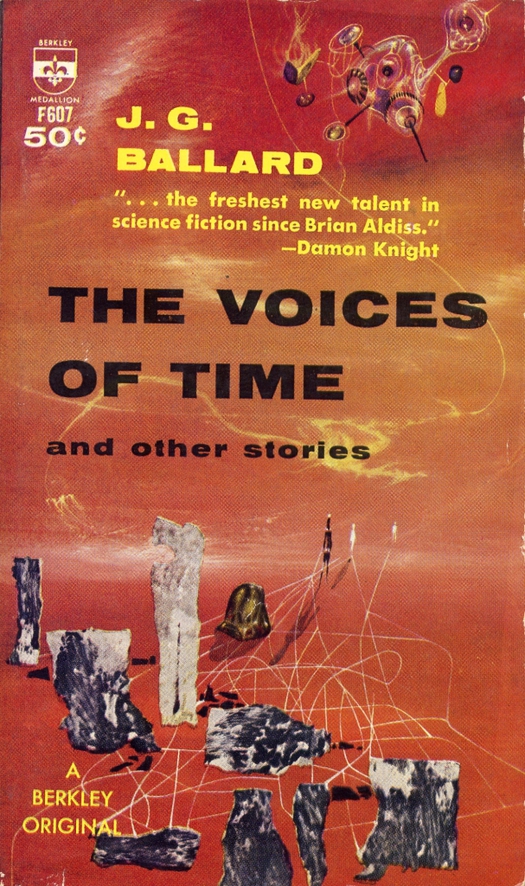

Richard Powers, The Voices of Time, book cover illustration, 1962

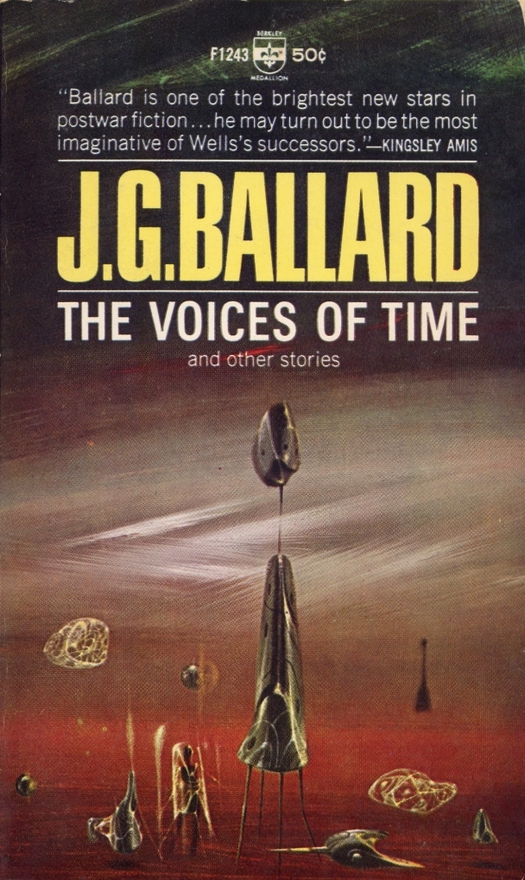

Each of the selected books was illustrated with a cover and these images, especially the early ones, are always a key part of the fun with surveys like this. For “The Voices of Time,” the paper showed the Berkley Original cover published in 1962, with an illustration by Richard Powers. The image doesn’t have much to do with the story, except perhaps as a tenuous visual metaphor, but I’m not going to object to that here. I rather like it. Powers was such an interesting artist that I’m prepared to see him as a book cover auteur who found opportunities — an astonishing quantity of opportunities — to express his vision for financial reward on the handy, ubiquitous tablets that paperback publishers duly provided. You might almost say that the books’ authors were lucky to get him. When The Voices of Time short story collection was reprinted by Berkley in 1966, Powers readily produced another cover image. Here again, he takes the infinite landscapes and near sentient abstract forms seen in the paintings of the Surrealist Yves Tanguy, which strange as they are, don’t necessarily imply we have left Earth’s atmosphere behind, and renders them incontrovertibly extraterrestrial.

Richard Powers, The Voices of Time, book cover illustration, 1966

Powers’ massive oeuvre of printed work can be studied online at the dizzyingly comprehensive Powers Compendium. The Guardian’s selection also included a 1953 cover for Clifford Simak’s City, when Powers’ work was still clunkily figurative and literal, if one can say such a thing about imaginary alien life forms. In later cover paintings, which are shown without type in The Art of Richard Powers by Jane Frank (2001), Powers constructs ambiguous pictorial spaces that seem to be both psychic and cosmic, molecular and planetary.

Richard Powers, The Shape Changer, acrylics on wood, 1973. For a novel by Keith Laumer

In The Shape Changer, a small humanoid figure glowing with light confronts an awesome vortex of rushing vapor and swirling space debris. There are smooth, pebble-like bodies inscribed with markings that could be floating talismans or alien space-pods, and a giant head veined with luminous threads that might be a living rock formation or an organic machine. Paintings like this recall the pulsating visionary art of the Chilean Surrealist Roberto Matta (see these galleries). Powers’ images, exercises in pure painting that constantly push towards abstraction, are far more suggestive than the naturalistic style of illustration (often by airbrush) that dominated SF book covers in the 1970s, not that art directors always seemed to know how to use Powers’ gifts. The Shape Changer was all but crushed by bizarrely over-emphatic typography, while an earlier image for the Science Fiction Omnibus (1963) — Action Painting meets mystical Surrealism — was heavily cropped on the book, stripping it of the full force of its vertiginous energy. Celestial beings once again merge with the fabric of space.

Richard Powers, Science Fiction Omnibus, acrylics, 1963. For an anthology edited by Groff Conklin

Earlier this year, the Courtauld Institute in London, a bastion of traditional art history and scholarship, held a conference titled “Surrealism, Science Fiction and Comics.” The single-day event probably attempted to cover too much ground — I would like to have seen fewer comics and more SF — but it was certainly a sign of the way that the study of Surrealism’s cultural impact continues to make connections with as yet barely researched areas of inquiry. The relationship between Surrealism and science fiction has the potential to be especially fertile and illuminating and one might have expected some consideration of Powers at the conference, but no one spoke about him.

Any future study of the interconnection of Surrealism and visual SF (particularly in the 1960s) needs to rectify this oversight. Jane Frank’s book has sections on abstract Surrealism and Surrealist techniques, and Powers, though by all accounts an elusive interviewee, was open about his visual influences and the sources for his stylistic experiments. Frank writes that, “he sought to penetrate a zone of discovery and revelation where there is no boundary between verbal and pictorial images.” The book is a fine starting point, but open-minded scholars more fully versed in Surrealism’s history and concepts would bring vital new perspectives.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rick Poynor

Related Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays

Oh My, AI

Recent Posts

What now? Make a Plan to Vote ft. Genny Castillo, Danielle Atkinson of Mothering Justice Black balled and white walled: Interiority in Coralie Fargeat’s “The Substance”L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save usRelated Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.