November 24, 2010

A Fluid and Expressive Medium: Interview with Robert E. Jackson

Since 1839, a cavalcade of photographic processes have framed our perceptions of images. Each time a new method evolves — from the daguerrotype to the gelatin silver print — something quicker and more affordable comes along. With the emergence of digital photography, what was once essential to “fix” an image — light sensitive material, substrate and chemical reaction — is no longer necessary. Ironically, now more than ever, historic methods have come back into vogue. Contemporary artists are embracing all things “alternative,” from cyanotypes to wet plate collodion prints, while methods that produce a signature format — a coloration and tonal range emblematic of a specific era — have joined with computer-driven technology to achieve new results that combine the best of both worlds. For example, it is now possible to digitally produce negatives (from imagery that is scanned or imported) and to customize the negative to work well in any photographic medium. All of which testifies to the fact that making photographs has been and is likely to remain in a constant state of flux.

Fixing an image to a page without the use of a camera as a mediating device has also remained a popular pursuit — from the photogenic drawings of Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) and the photograms of Anna Atkins (1799–1871), to Man Ray’s rayographs (1890–1976) and the camera-less works of Adam Fuss (1963– ). Process may be an impetus, but no one tool or technique is sacred. It is our quest for the final arrested image — not the means to its capture — that sets us in motion.

In recent years, a new breed of photographer has emerged: the camera-less photographer. This new generation — many of whom self-identify as collectors — has reinvented the process once again: theirs is a practice which might be best characterized as hunting, appropriating and editing to obtain a certain kind of image. Such idiosyncratic makers/collectors have evolved as a sub-genre within the ranks of the amateur, whose collective output has spawned a revolution in the creation of a kind of new, tactile imagery. Without fanfare and well beyond the purview of what most people believe constitutes an artist, this new pioneering practice creates from an already existing body of work.

Following in the modernist tradition of the readymade, the practitioners of this form of photography hunt and seek images in much the same way as photographers did long ago, with one big exception: they don’t actually need a camera. The image has already been taken, and a full arsenal of photographic tools have been employed — but all of this has been achieved by someone else. The image has been processed, but lies dormant, like unexposed film in the can. Not unlike a print awaiting its expected gestation (which occurs only when submerged it in a chemical bath), such images remain unformed, until these new image makers — no longer selecting from a day’s shoot, a contact sheet or a digital file — uncover and choose from existing prints. Tirelessly scouring the marketplace — both online and on foot — their goal is to fix an image (untethered to an author) by plucking it from the past and, in a very real sense, recontextualizing it. Through this new breed of photographer-hunter-artist, found snapshots become a rich resource for self-expression.

To mount its 2007 exhibition, “The Art of the American Snapshot: 1888–1978,” the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. drew entirely upon the resources of collector Robert E. Jackson. Jackson is an avid and prolific compiler of vernacular photography, who lays claim to a breadth and depth of material rivaled by few (if any) in this emerging field. Jackson worked with the National Gallery in selecting images for the landmark show — an overview of the changing perspective of the amateur photographer in America over a period of nearly 100 years — culling over 200 photos from a collection that then numbered approximately 8,500 images. His aesthetic approach to the snapshot acts as portal to the lyrical, humorous and transcendent nature of the medium. Delving into the images he has amassed, one discovers a highly evolved creative process and logic at work.

Michelle Hauser:

Robert, you have stated that snapshots are “a fluid and expressive medium.” Can you elaborate?

Robert E. Jackson:

They are generally expressive of a narrative content that the collector is often at a loss to understand when attempting to “read” the photograph. The snapshot is a malleable medium that can be used to impart many things to many people. In my mind, the main impetus in taking a snapshot is to record and establish some narrative structure around the events of one’s life. The photo existed for the snapshooter, or for the person whose life is being recorded in the photo, as a surrogate for memory, such that in time the photo becomes the memory. But when viewed by the collector, who has no knowledge of the events being recorded or the impetus for the taking of the photo, the snapshot can come to be seen as an aesthetic object expressing many things. Also, through a typological construct of snapshots on a related subject, an entirely new photo piece can be created that has nothing to do with the original snapshots’ intent.

MH: Do you ever feel like you are collaborating with whoever took the snapshot, or is it yours now entirely?

REJ: These snapshots now exist in my collection without the weight of any of the narrative import that accompanied the taking of the photo. I am interested in the formal aesthetic qualities of the photo and have no interest in trying to place when and where it was taken. Or what the photo meant to express or record. What is important now is what it means to me and how it might fit within a larger typological framework.

MH: Marcel Duchamp once said, “Art is either plagiarism or revolution.” How do you respond to this notion in light of what’s happening within the context of your collection?

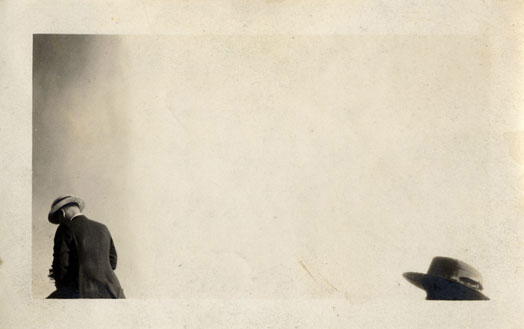

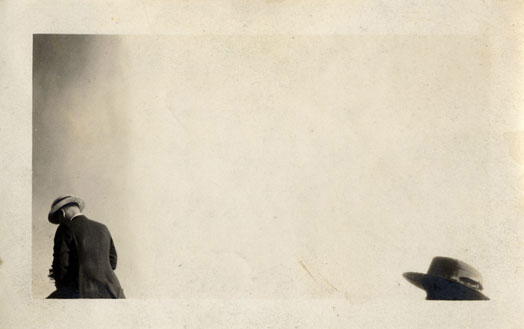

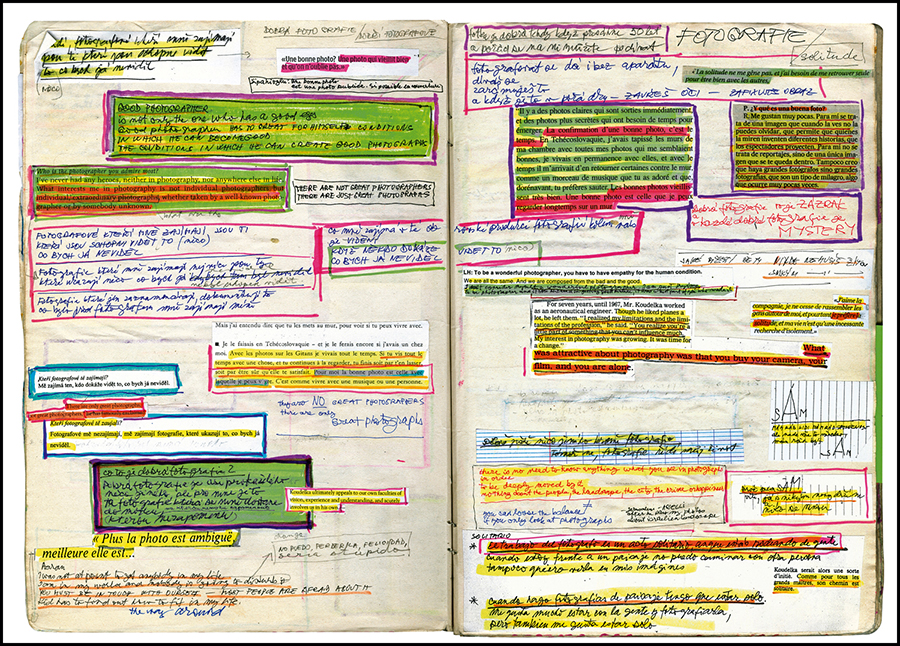

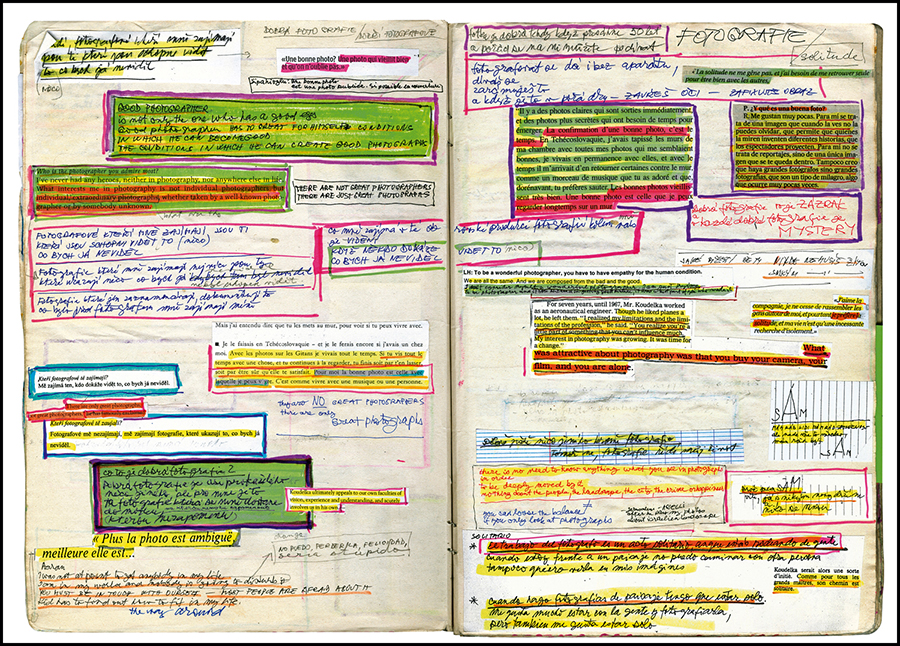

REJ: Well, it must be established whether these snapshots are considered art. Where the art perhaps comes in is what I do with the photo. How I might pair it with another, or how it relates to other photos that involve a similar trope (i.e., taking a photo of something through a chain-link fence, for example). Is what I am doing “revolutionary?” No. But is it important? Maybe. My collection might force people to look at snapshots differently and that might be considered something new. Or it might expand what is considered as a snapshot. The photos used to illustrate this interview don’t fit what most people think of when they think of a standard snapshot.

MH: It appears that you have collections within your collection, and I’m intrigued by some of these: tell me a little more about the ones you refer to as “Pure Photography.”

REJ: Within the body of snapshot imagery contained in my collection, there is a subcategory of photos that provide few to no clues as to why the photo was taken or what is occurring within the borders of the photograph. Thus the photos come close to being what I call “pure photography” in that they can be viewed purely as aesthetic objects. The photos exist for their own sake, with no apparent narrative strand that can be used to “read” the photo. The subject of the photo is what the viewer (or collector) perceives it to be. The photo thus stands independent of any associative imagery and the tropes of previous snapshot subjects. Notice the photos featured here: They are all form and little content. They don’t relate to time or place. They are stripped of associative snapshot imagery and thus exist as a pure piece of photography.

MH: Your “pure photography” snapshots reflect the surreal intersection between consciousness and sleep, realism and abstraction. Artists in other mediums often try to achieve some of the things that are captured here. Do you find yourself seeking this experience in other art forms, such as painting, for instance? Or literature or film?

REJ: No, if you mean by “experience” a desire to collect such a “pure” visual phenomena in other areas. I respond to the visual nature of photography in ways I don’t respond to other art forms. I think the language of snapshot photography speaks to me in a personal way that I often don’t find in most literature — although poetry comes closer to the spirit of some snapshots in the usage of words and sound imagery to create something that transcends the concrete narrative of prose.

MH: Tell me a little bit about your background. What started you on this path? Was there a first photograph that started it all?

REJ: I have been collecting snapshots for over eleven years. Other areas of interest are cabinet cards, arcade photographs and photo collages from the 1870s through the early decades of the 20th century.

I have a background in Art History as well as an MBA. When I began being interested in photography, snapshots were more accessible and affordable to me than other areas within the genre. I liked the quirky nature of the material, the odd angles, the blurred sense of movement, double exposures, the mystery of life’s small moments, which can be found within the borders of the pictures. There was no “first photo” which started this obsession. I came to love the possibility of what I might find in a snapshot after looking through bins and boxes of snapshots at flea markets and antique stores and being exposed to other people’s amazing collections.

MH: About how many photos will you review before one makes the cut? Are you seeking something specific?

REJ: I look at a lot of photos. Probably for every hundred, I might find one to purchase. I am looking for an image that speaks to the inventiveness of photographic intent, or an image where two or more elements that you would not expect to see together in one photo are in fact depicted (like a woman holding a baby lion on a street corner, for example), or an image that has a strong visual impact at first glance. I like images that surprise, make me laugh out loud, or have a mystery or stillness to them.

MH: You continue to hunt and acquire more work. How large is your collection today?

REJ: I have around 11,000 snapshots presently. I have the photos in books, which hold a hundred photos, one to a page. The books are all numbered. I have organized my collection in order of when I purchased the photo, but lately I have been interested in taking the collection apart and looking at it via subject types. I have books on double exposures, people in mirrors, people lying down with their feet being the dominant image, trick photos, people in masks, diving photos, as well as a book on photo silhouettes. Looking at photos of a certain subject all together helps to cull out the weaker ones. Color photos go in separate books and I have different books for horizontal versus vertical photos. The larger the collection, the more one begins to notice certain themes: for example horizontal snapshots are much more narrative than vertical snapshots. Vertical snapshots, however, are more common — at least they are in my collection. I have approximately 3,000 horizontal photos versus 8,000 verticals.

MH: Do you have any plans for your collection at this time?

REJ: I would be willing to part with some or all of them, if the appropriate situation arose. I might draw photos from my collection; for example, to create a small carefully selected snapshot collection for someone who wished to have a nice representative selection of snapshots within a larger photographic collection. I continue to remove photos, which now seem weak in comparison to others I have recently collected. A collection is a living and evolving organism, in my opinion needing pruning and care. As an adjunct to my snapshot collection, I have over 130 books, articles and dissertations related to snapshots, which I hope one day will find a home in a scholarly archive devoted to snapshots and vernacular photography.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Michelle Hauser

Related Posts

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own path

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Josef Koudelka, Next: A Visual Biography: Ten Questions for Melissa Harris

Sustainability

The Editors|Interviews

GOOOOOOAL

Books

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Henry Leutwyler: International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum

Recent Posts

The Design Observer annual gift guide! ‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison ‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change Gratitude? HARD PASSRelated Posts

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own path

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Josef Koudelka, Next: A Visual Biography: Ten Questions for Melissa Harris

Sustainability

The Editors|Interviews

GOOOOOOAL

Books

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Michelle Hauser is a visual artist living in Maine. Along with her partner, Andrew Flamm, they founded

Michelle Hauser is a visual artist living in Maine. Along with her partner, Andrew Flamm, they founded