September 7, 2013

Bohumil Stepan’s Gallery of Erotic Humor

Galerie by Bohumil ŠtÄ›pán, published by Mladá Fronta, Prague, 1968. Photograph: Mapp Editions

The Czech curator Marta Sylvestrová introduced me to Bohumil ŠtÄ›pán’s book Galerie while we were working on my Uncanny exhibition. It’s a great example of the way that Surrealist influences permeated Czechoslovakian visual culture in the 1960s and I wanted to include it immediately. Displaying books is always problematic in exhibitions because even with two or three copies to work with only a glimpse of the whole can be shown. Old copies of Galerie, published in 1968, are not hard to find in the Czech Republic so we decided to make a curatorial exception, throw conservationist principles to the wind, and sacrifice a couple of copies for the sake of the show. We mounted all the pages on card and displayed them on the wall in long rows, so that viewers could experience the entire publication as it was originally printed. Seen in such profusion, the exuberantly melancholy eroticism of ŠtÄ›pán’s collages and drawings had enormous impact.

Detail of Galerie on show in Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design, Moravian Gallery, Brno, Czech Republic, 2010

Photograph: Archive of the Moravian Gallery

It’s now possible to view Galerie much more easily thanks to Mapp Editions, which was founded in 2011 to produce digital versions of outstanding printed works. Mapp’s smartly curated list includes books about art, design, photography, the humanities and sciences, and ranges from historical curios such as the Atlas photographique de la lune to Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s highly regarded War Primer 2. The images of Galerie here are from the Mapp version, which came out a few months ago and runs on the iPad, Mac and PC.

ŠtÄ›pán (1913-85) is one of those figures — there are so many in the applied arts — about whom little appears to have been written, even in Czech; there is nothing substantial about him online in English. He was born in KÅ™ivoklát in Central Bohemia and studied at the Ukrainian Academy of Fine Arts and the private Rotter Advertising School in Prague before becoming a painter, graphic artist and illustrator. In the 1950s, during the Cold War, he produced communist propaganda and worked as a cartoonist for Dikobraz (Pineapple) magazine. In the early 1960s, like other Czechoslovakian graphic artists, he designed film posters that combine drawn and collage elements. Collage became his focus and his collage-drawings and cartoons appeared in publications such as the satirical magazine Trn (Thorn), Mladý svÄ›t (Young World) and Plamen (Flame), a literary magazine. His book projects based on this style include PraštÄ›né pohádky (Wacky Fairy Tales, 1965) by Ludvík Aškenazy and Gulliverovy cesty (Gulliver’s Travels, 1968). The Terry Posters website has a good selection of book covers, illustrations and posters. In 1969, ŠtÄ›pán emigrated to Munich, where he had a second career illustrating books and magazines; this also calls for research. Publications from his German period include a book of cartoons (1970) and Familienalbum (Family Album, 1971) composed in the surreal collage style of Galerie — it features a few of the same images.

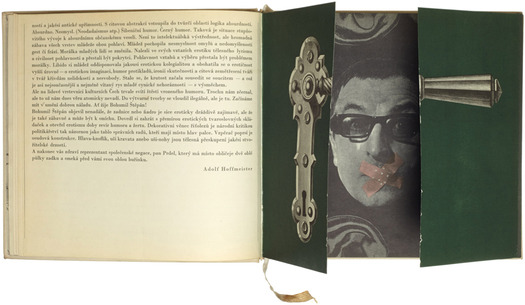

Galerie by Bohumil ŠtÄ›pán. Photographs: Mapp Editions

Galerie, printed in black and sepia with occasional accents of red and green, has a darker atmosphere than other projects by ŠtÄ›pán and it feels older. It shares the Surrealists’ love of the antiquated and outmoded revisited through modern eyes and made strange. The photographs, objects and clothing styles come from decades earlier and the repeated use of picture frames around ŠtÄ›pán’s images emphasizes their archival nature. The book arrived during a period of social and political liberalization that culminated in the “Prague Spring” of 1968, which was then crushed by the Soviets. In these years, the arts flourished in Czechoslovakia and the styles in fashion and popular culture were much the same as the West’s. Galerie expresses its modernity by using the freedoms of collage as a vehicle for the entirely contemporary topic of Erotický humor (erotic humor) — the title of the artist Adolf Hoffmeister’s introduction, which Mapp has translated. The old taboos have disappeared, declares Hoffmeister, and literature can deal with subjects once confined to forbidden works of pornography: this was Surrealism’s lesson. Hoffmeister provides no antecedents, but Czechoslovakian Surrealism of the 1930s displayed a notable sexual frankness. “The morality of youth has changed,” he concludes. “In their relationships they have found the eroticism of corporeal lyricism, they have accepted the civility of sexuality, and so they have ceased to be hypocrites.”

ŠtÄ›pán’s “gallery” is framed as an unapologetic attempt to sell the work on display — the later sales history of several pieces can be traced through auction house websites. A door opens and we meet the jocular, bespectacled artist, his lips sealed by Band-Aids, announcing the sale of his work. Over the page, Rosa and Josefa, a pair of conjoined twins, cavort at the gallery opening. A series of aerial photos purports to show the mounting crush of visitors at the opening and a note says there are still pictures available. This sardonic mood pervades the book, through to the back cover where ŠtÄ›pán has collaged himself and his wife, Hana ŠtÄ›pánová, the book’s graphic designer, into an uncredited production still from Todd Browning’s notorious film, Freaks. In a speech bubble, which is the only cover blurb, he describes the circus sideshow people as his “family circle.”

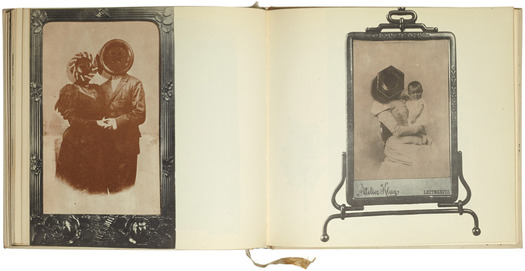

Galerie by Bohumil ŠtÄ›pán. Photographs: Mapp Editions

Would we call the book sexist now? Certainly it seems to dwell on a glum if not jaundiced view of heterosexual masculine experience, which is portrayed in many images as a kind of slavering servitude to women that doesn’t do its sufferers much good. Some of ŠtÄ›pán’s men are simply gawking: one peers down a bra; another, with a head made of buttocks, fixates on a woman’s behind; a third sits down to relax in a chair formed from a female torso. One frisky fellow wants to find a body-shaped lock for his body-shaped key. The man pierced by a giant knife bearing images of three women’s heads might be unlucky in love, or a serial cheat who got his comeuppance. For the guy with a noose around his neck swinging from a nipple, there is clearly no way back. The biggest image of a female face in the book has man-spearing fish hooks in the voids where her eyes ought to be. ŠtÄ›pán has an experienced cartoonist’s economy and quickness of line, moving between drawing and collage with a perfect sense of poise. He makes these often desolate scenes — broken axes, decapitations, a brain in a cage — look much more light-hearted and tolerable than the bare facts sound when recited.

Galerie by Bohumil ŠtÄ›pán. Photographs: Mapp Editions

Galerie by Bohumil ŠtÄ›pán. Photographs: Mapp Editions

It isn’t all bad news for the concupiscent male and his quarry. Some degree of domestic détente seems to be achievable. A formally attired couple cuddle up for the camera, although clothing buttons obliterate their identities (they are both literally and figuratively buttoned-up), and a similarly faceless mother nurses a child. It might be possible in 1968 to be outspoken about the erotic life, but in ŠtÄ›pán’s world still mired in culturally ingrained and hard-to-escape habits of sexual interaction this loosening-up doesn’t necessarily equate with blissful emancipation.

The Mapp presentation is the next best thing to owning the book. The only element they haven’t been able to reproduce is the big cutout of a thumb, which came with Galerie as a bookmark.

Thanks to Marta Sylvestrová

See also:

Bohumil ŠtÄ›pán’s Family Album of Oddities

Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design

A Dictionary of Surrealism and the Graphic Image

Slicing Open the Eyeball: Surrealism and the Visual Unconscious

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rick Poynor

Recent Posts

The New Era of Design Leadership with Tony Bynum Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature A Mastercard for Pigs? How Digital Infrastructure is Transforming Farming and Fighting Poverty DB|BD Season 12 Premiere: Designing for the Unknown – The Future of Cities is Climate Adaptive with Michael Eliason

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.