August 14, 2019

Depero’s English Pictionary

Earlier this year I wrote an essay for the exhibition and book Italian Types: Graphic Designers From Italy In America (Corraini Edizioni) curated and edited by Patricia Belen, Greg D’Onofrio, and Melania Gazzotti. My topic: to compare the New York experiences of two very unique multi-disciplinary designers, Paolo Garretto (1903–1989) and Fortunato Depero (1892–1960). I wrote:

In late 1920s–1930s the Italian artists Paolo Garretto and Fortunato Depero briefly lived and worked in Manhattan, contributing to a modern graphic design aesthetic that was shaped by European immigrants. Despite their proximity, Garretto and Depero are rarely studied together — yet when viewed together from a contemporary perspective it is clear that their work, each in its own way, informed the visual zeitgeist of their times (and history of graphic design).

I noted that Garretto, with whom I corresponded for two years prior to his death in 1989 in Monaco, spoke and wrote fluent English and that Depero, as far as I knew, did not — although he did self-publish an awkwardly translated English edition of his 1947 autobiography, So I think, so I paint: Ideologies of an Italian self-made painter.

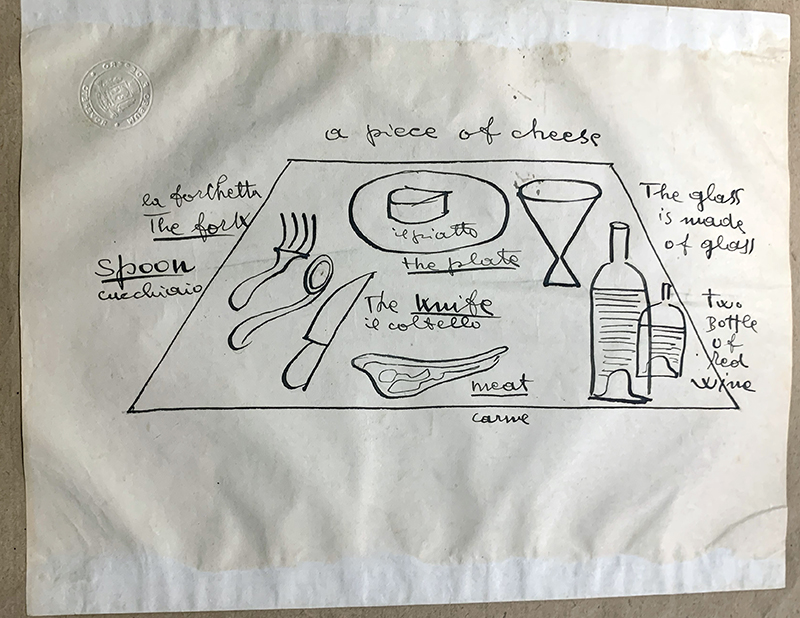

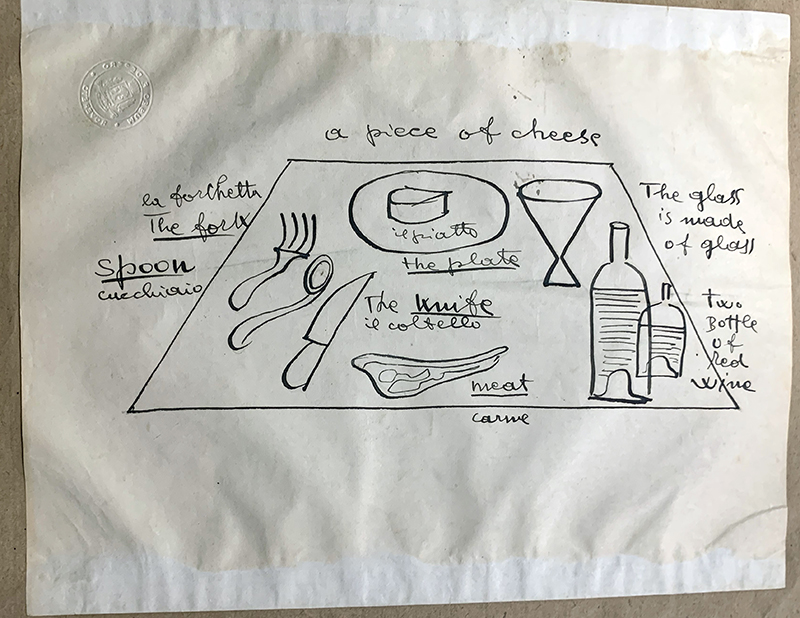

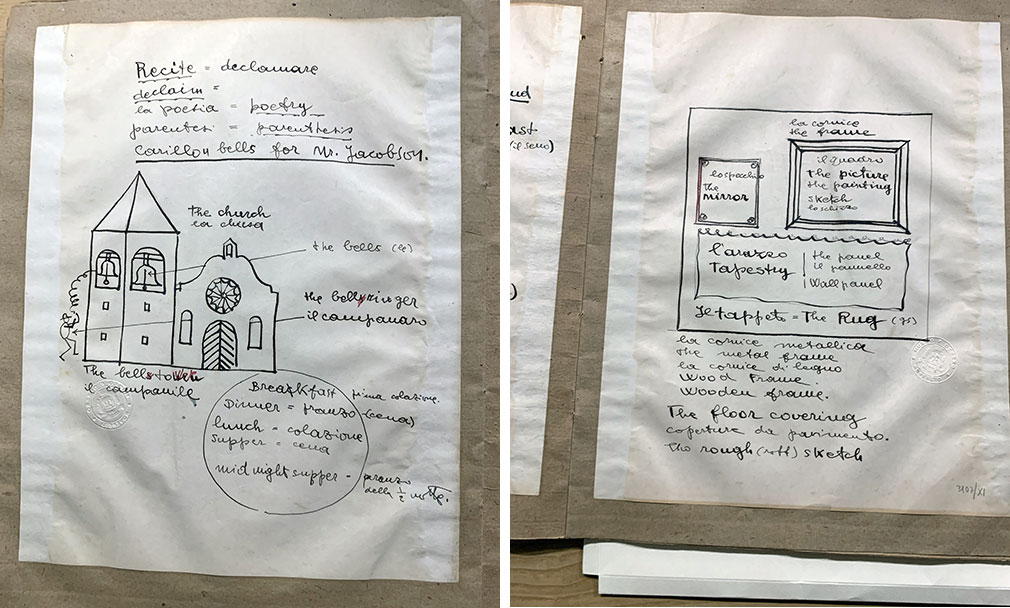

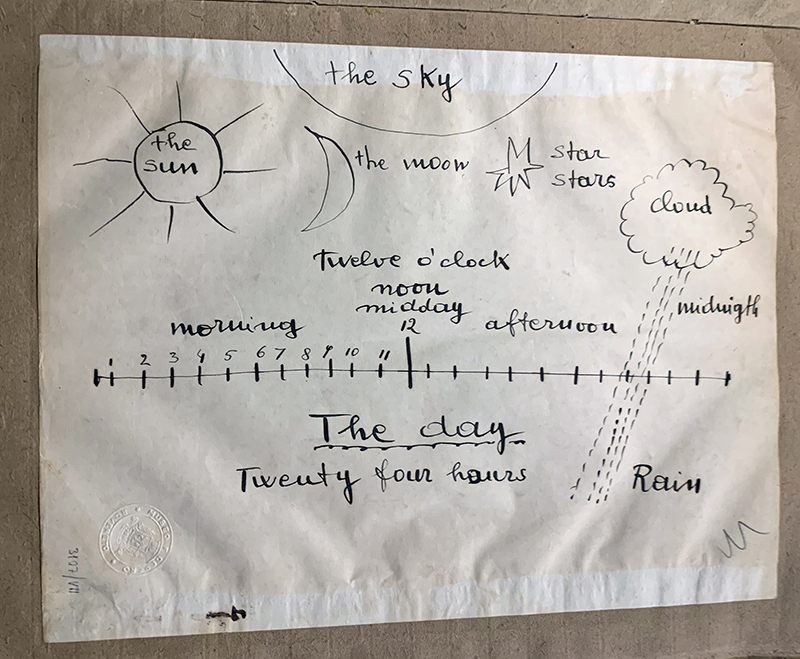

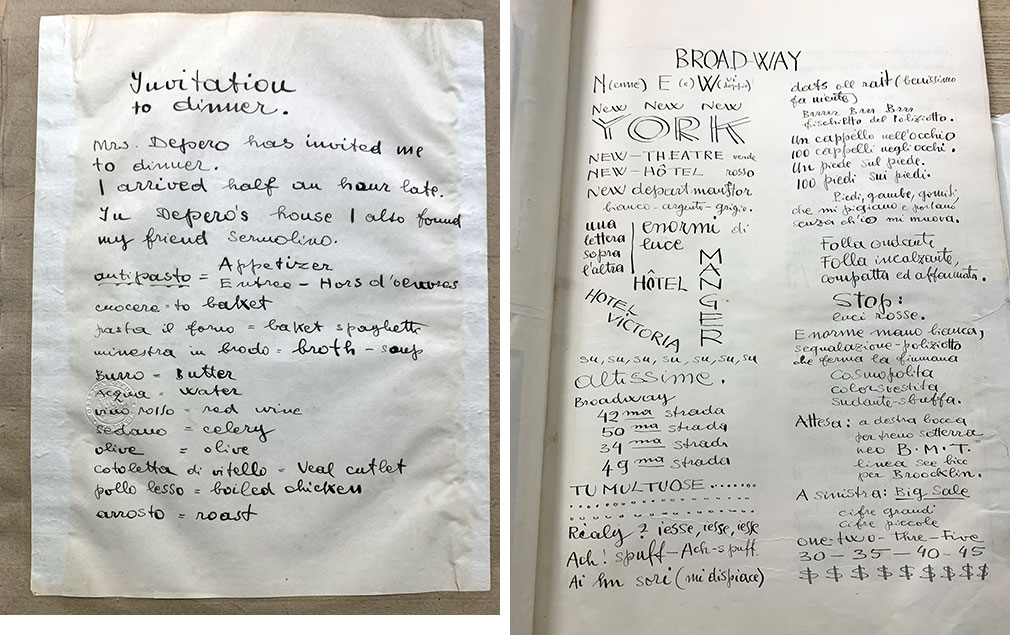

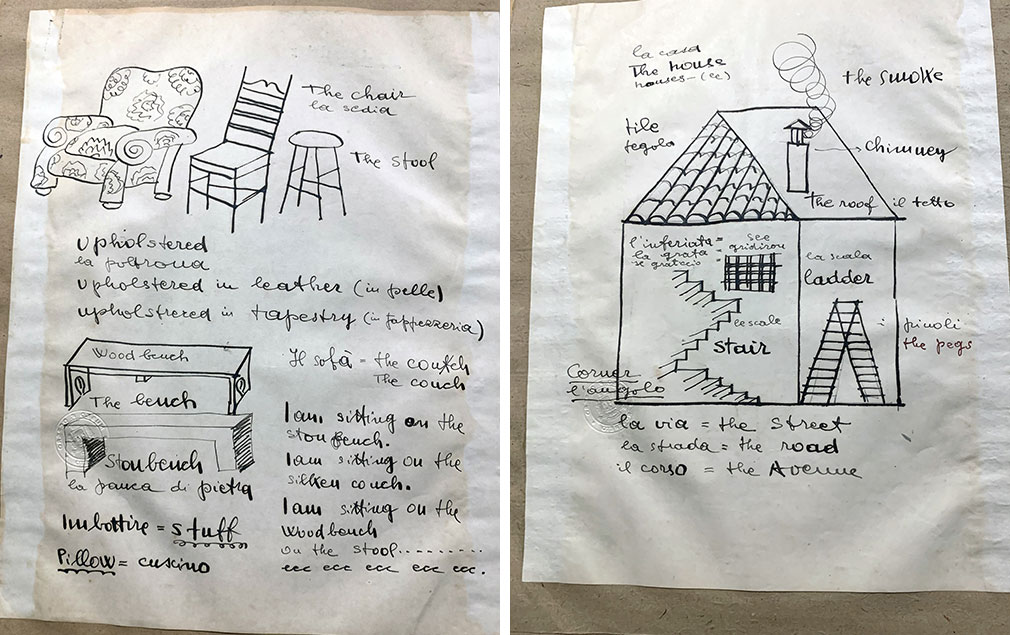

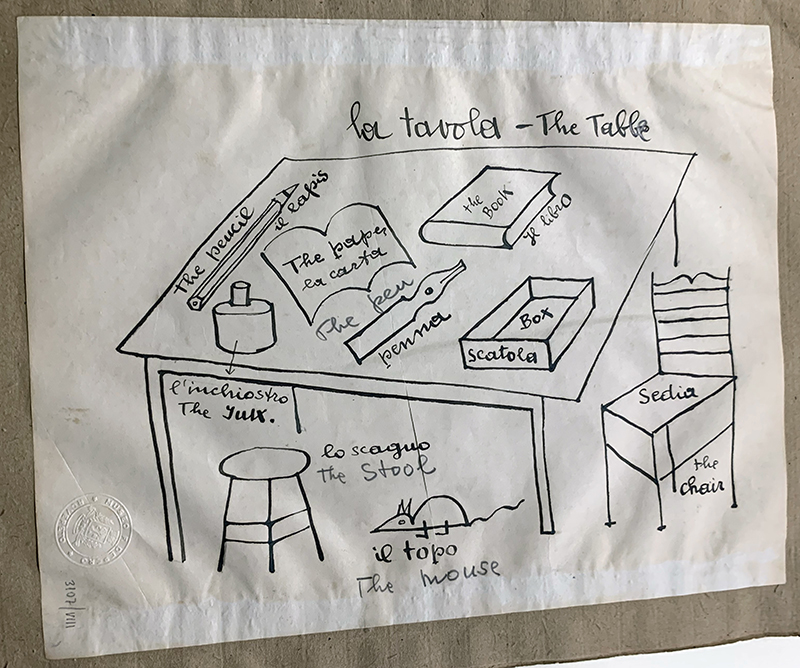

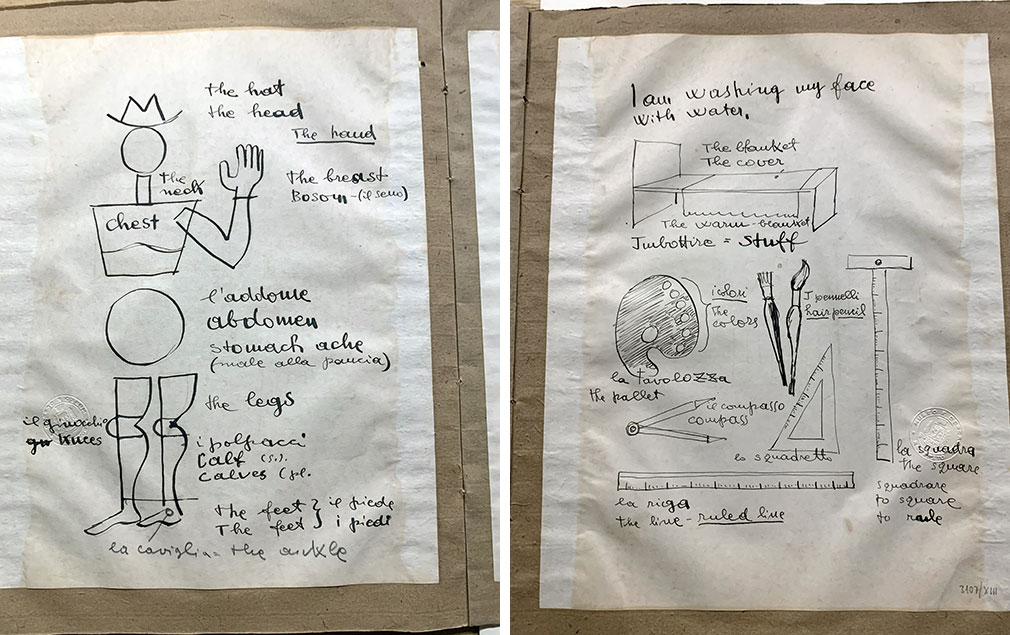

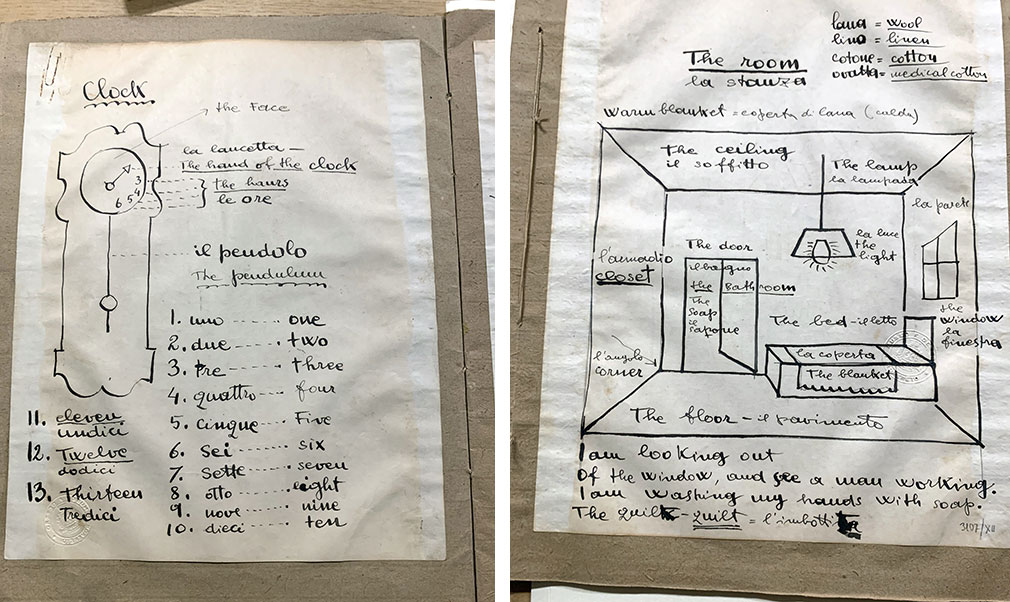

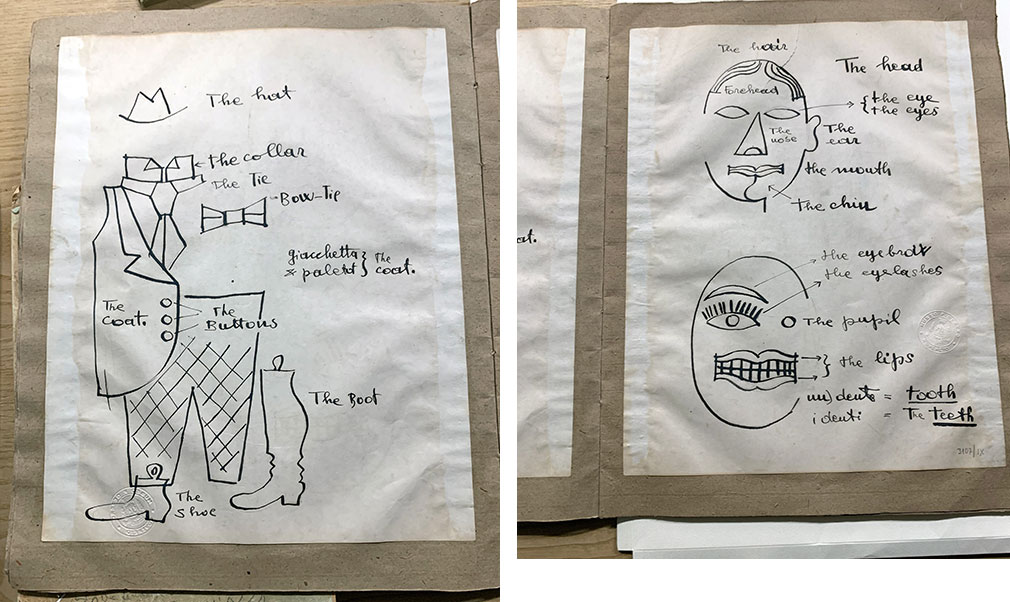

This summer, while visiting The Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero and the nearby Depero Archives at MART (Il Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto) I was pleasantly — no, elatedly — surprised to find a small treasure that, if I had access to it, would have added more valuable nuance to my essay. Depero had created a pictorial dictionary (pages of which I present here) as a personal Pictionary-esque learning aid. The hand scrawled script and simple line drawings explores a range of linguistic necessities like human anatomy (describing a “stomach ache,” distinguishing “lips” from “teeth”), animals (describing the anatomy of a bird), food, furniture, the layout of his bedroom, and so on.

Years earlier I had uncovered a copy of his autobiography, which contributes more information to the first of two periods when he took up residence in New York. Why this is of interest now (you might wonder) is in part owing to a renewed appreciation for Depero’s work, particularly with the reprint two years ago of his famous “Bolted Book,” an icon of Modernist book design, an exhibition in 2017 at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York, and the visionary contemporaneity of his applied and fine art from the 1920s and 30s within today’s design milieu.

Sailing to New York with his wife Rosetta and copies of the Bolted Book, he was determined to make a bigger name for himself as artist and designer, while promoting Futurism. “Before going to the States,” he wrote in his autobiography “I was told that Americans do not understand much of art. Undoubtably [sic], they devote themselves more to business and practical problems than to art and spiritual problems. But I must truly say, for instance that critique in New York is signficative [sic] for its unprejudiced, objective, clarifying, and faithfully fulfilling its purpose.”

About his challenges with language fluency he added: “In New-York [sic], I had to fight against many difficulties, all because I could not speak English. I can, however, make myself understood in German and so I was able to speak with managers of theatres, secretaries of galleries, critics, people belonging to the artistic world, and Jews knowing German. I found, in them, sympathy and understanding for they are clever and interested in everything. I also found in them, real practical help and therefore I always remember them gratefully. . .” Continuing a list of minor obstacles, he further noted: “I was also obliged to struggle against the continental climate, terribly cold in winter and tropical in summer, a climate in which we Italians can hardly breathe, used as we are to mild temperate weather . . .”

Depero came to New York on two occasions. The first, from 1927 to 1930, was the most productive. He opened his Casa Futurista Depero (Futurist House) in The Transient Hotel at 464 West 23rd Street (the building still stands) and Rosetta prepared Italian feasts to court the buyers, critics, and press. “During this time I set up seven personal shows,” wrote Depero. “The press took much notice both of my decorative art and of my painting. The famous critic Christian Brinton [(1870—1942), an internationally noted critic, collector, and curator, who participated in the promotion of modernism between 1910 and his death] introduced me to the public and the most important newspapers. He also wrote the introduction to one of my catalogues in which among other things, he says ‘Depero created organic plastic dynamism transcending beyond specific groups and possessing a rhythmical vibration and an esthetic manner of its own.’”

These pages in the collection of the Depero Archives underscore the artist’s tenacity and humor. He did find some commissions in New York and produced a respectable amount of work before heading back to Italy. But he never achieved the success he or Rosetta had hoped for.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Recent Posts

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,