December 31, 2009

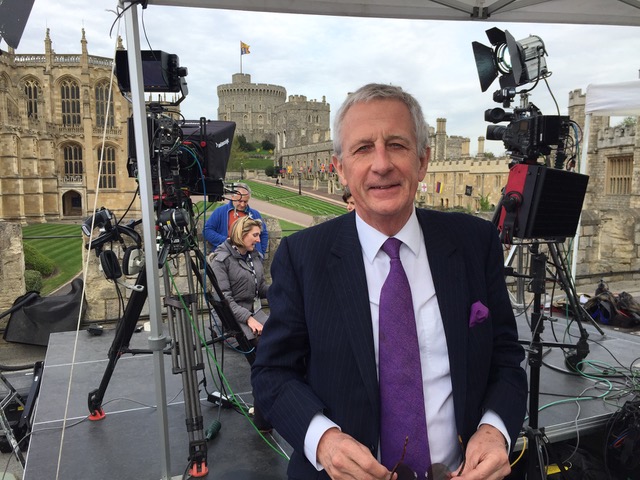

How Advisor to The Crown Robert Lacey Gets Closer to the Truth

In this limited series, Design Observer features conversations with creatives that have gained a foothold within the bustling London design community. Interviewer and author Lily Hansen takes conversation with others from chore to professional vocation, and as oral historian Studs Terkel put it, talks with creative people “about what they do all day and how they feel about what they do.”

We selected five such conversations—with illustrator Ella Paton, author and science communicator Kat Arney, filmmaker Rob Petit, historian (and consultant to the Netflix series The Crown) Robert Lacey, and toy designer Luc Hudson—to enlighten us as to what they do, why, and how they found their creative voice within the cultural crossroads that is London, England.

Robert Lacey is a British historian and the author of numerous international bestsellers. Published in 1977, Majesty—his pioneering biography of Queen Elizabeth II—remains acknowledged as the definitive study of British monarchy. The Kingdom, a study of Saudi Arabia published in 1981, is similarly acknowledged as required reading for businessmen, diplomats, and students all over the world when traveling to or studying the subject of Saudi Arabia. Like The Kingdom, his follow up Inside the Kingdom has been banned from distribution in Saudi Arabia by the Ministry of Culture and Information. Robert’s many other books include biographies of the gangster Meyer Lansky, Henry Ford, Princess Grace of Monaco, and a study of Sotheby’s auction house. He is the lead historian for the Netflix series The Crown.

I just wanted to start off by asking you a very simple question. When did you realize you were passionate enough about writing to make it into a career?

I always enjoyed writing—mostly historical. I loved reading the great English and American writers. I suppose when I look back on it, Cambridge was a very good preparation for what I do now in terms of the tutorial system of history. At the beginning of the week we were presented with a proposition about what you know virtually nothing. At the end of the week you have to be an expert and present your argument to the supervisor face to face. To do that weekly was very good training to become a sharp-eyed critic in terms of the evidence and logic of everything that you write. It was a marvelous apprenticeship for journalism, history, biography depending on where you put it in the scale.

Did you learn to make really fast decisions?

Yes. And it shaped my reading habits. I really can’t read for what most people call pleasure. I’m now reading great books about politics in Britain in the 1950s and ‘60s, all of which I need to help with my current work as historical consultant on the Crown for season three. That set a pattern which has never changed. Intense reading became a more edited version over time to find out what I wanted to concentrate on. I also learned how to write under quite high pressure. I never imagined that I could make a living as a writer. I trained to be a history teacher, which I did for some time in South London. I was also offered jobs in the British foreign office and the British foreign council.

By willy nilly I found myself as a professional writer and have managed to do that ever since.

Purely by chance, love intervened with a South African girl because I used to work on my vacations as a travel courier. I would take Americans in the summer and South Africans in the winter around Europe. I wanted to go back to South Africa to see my girlfriend and couldn’t afford it. Just at that moment the Sunday Times color magazine, which was the first, ran a competition for young writers, photographers, cartoonists, and fashion designers. The prize was an air ticket anywhere you wanted in the world. I had to write a 2,000-word piece about a living person, which was the first time I realized that I only write to commission. I don’t sit down and write for hours about my thoughts or how to put the world to rights.

While I didn’t win, I was one of the finalists and won 80-pounds, which was enough to fly to South Africa where I got to work in Johannesburg at the Sunday Times. I wrote think pieces about South Africa, which were on the whole about how much I hated it. The romance sadly did not flourish, but my writing career did. When I came back I wrote my first book. By willy nilly I found myself as a professional writer and have managed to do that ever since.

How did you develop your own style of biographical writing?

In order to write about the monarchy, Saudi Arabia, and the Ford family I deliberately tried to immerse myself in those worlds. Majesty was a tremendous yet surprise success, because most people weren’t interested in the queen at the moment. After that, lots of publishers wanted me to write a book about Charles II, which I felt would typecast me. No thank you. In the late 70s, Saudi Arabia was on everyone’s lips in the way that ISIS is today. I felt there was also a modern, cohesive history there about how the kingdom was created and battles were fought. It was also hard to get in and through serendipity, I met a young Saudi who said he would give me a Visa to come and work in Saudi Arabia. I couldn’t speak any Arabic and had no background whatsoever in the Middle East. The only way I could compete with other academics and journalists was the advantage of being able to live there. Getting to know the smell and scent of the place by living there with my family was what I brought to the book.

The Kingdom captures the romance of that institution whether you love or loathe it. The added bonus was that the book was banned in the Middle East, which gave it great credibility and cache in the West. They came up with 97 complaints about the book, which was very flattering. Apparently I had failed to understand Islam because I’m not a Muslim. Still, I felt that I gave the best insight that I could into the country’s beauty, conflicts, and shortcomings.

How did you learn to take criticism as a compliment?

I felt that I had obviously been doing something right if I pressed their buttons. A committee of scholars had spent all of this time analyzing my book, which was quite amazing. Every setback has a purpose and you can learn from everything, can’t you?

Every setback has a purpose and you can learn from everything, can’t you?

Clichés are true for a reason. What do you think it is about your personality that allows you to really hit the nail on the head?

I’m sure it goes back to the British historical education as inculcated to me first at Bristol Grammar school and then at university. Working on The Crown, which is a drama series rather than a documentary, some characters are invented even though the series relating history. They are an amalgamation of all the people that writer Peter Morgan and the research team studied for the series. Peter is brilliant at turning clichés on their head, and I have learned a lot from him.

How do you know what the truth is? People’s memories are slippery.

There you go. As someone I very much admire, Hilary Mantel, says, “The past is not history. History is the method we have evolved for handling our ignorance about the past. Ninety-five percent of the past is what people said to one another or dreamed has vanished. All we have left are a few documents, which are essentially a few pebbles, which the historians pick out.” Macbeth did not kill King Duncan in his castle. He killed him on the battlefield as far as we know. Shakespeare’s imagination brings the past to life in a different life. It’s totally legitimate.

I’ve read you also show your subjects the material you extract from them during interviews, which is unusual.

Everyone I write biographies about, whether full-scale or miniature, are people I love and admire. The images that I paint of them are positive. I am drawn to each of them in different ways. I love the textures of the environments in which my subjects flourish, which is why I like to think I’m not a snob. I love the upper-crust environment in which the queen operates but I equally love the semi-criminal subculture of South Florida. In terms of showing my subjects the work, I see this method as common courtesy. If someone is giving an interview they are taking a chance. I don’t guarantee everything the subject wants changed and have had quite fierce arguments when I know I am sure of my facts or interpretation. I do my best to reflect my subject’s lives but there are also multiple truths. You try to define what they are and assemble those different interpretations. Although I do find it funny, the great delight people seem to take in pointing out your mistakes to you.

I do my best to reflect my subject’s lives but there are also multiple truths. You try to define what they are…

Do you trust your intuition in terms of making interpretations about an event or a subject’s life?

I trust the instinct that allows me to devote three, four years of my life to a subject.

A lot of young writers believe they have to put out a tremendous amount of free material in order to gain any success. Where did your sense of self-respect come from in terms of only writing for pay?

Obviously I hoped for good reviews in terms of my books but my real dream was to be a best-selling author. Tens of thousands of people enjoying a book of mine was something I considered very valid—that what mattered to me resonated with other people was huge. Then the success of one book would inform the next.

What is one of the most interesting moments of your career?

For one project I used the Freedom of Information Act, which is an amazing process because after you submit your request, about a year later, a huge package of documents arrives at your doorstep. Much of the material is solidly blacked out, which is obviously where the truth is. There are writers who make entire careers around speculating about sinister ideas in the blacked out material. On the other end, I feel justified debunking great myths, which most people don’t want unraveled. People would rather live with their conspiracy theories, which instead of looking at the history leading up to an event, studies who was the beneficiary.

I feel justified debunking great myths, which most people don’t want unraveled.

What is your personal philosophy that you lean on when things aren’t going so well?

Anger, a “poor me” attitude, and resentment don’t help. Even though it sounds a platitude, there are positives to draw from any situation. If things aren’t going so well there’s a reason for it. Most problems can be seen in a positive light.

What is your favorite thing about what you do?

The feeling that I am getting closer to truths that teach me things and hopefully help my readers. Now whether my total immersion in the study of other people’s lives has led me to ignore or miss truths about my own life is another question. But for the moment, I find discovering the truth about others to be very satisfying for myself.

This interview has been edited for length. Read even more from Lily Hansen in Word of Mouth: More Conversations.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Lily Hansen

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

The face, reconsidered

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

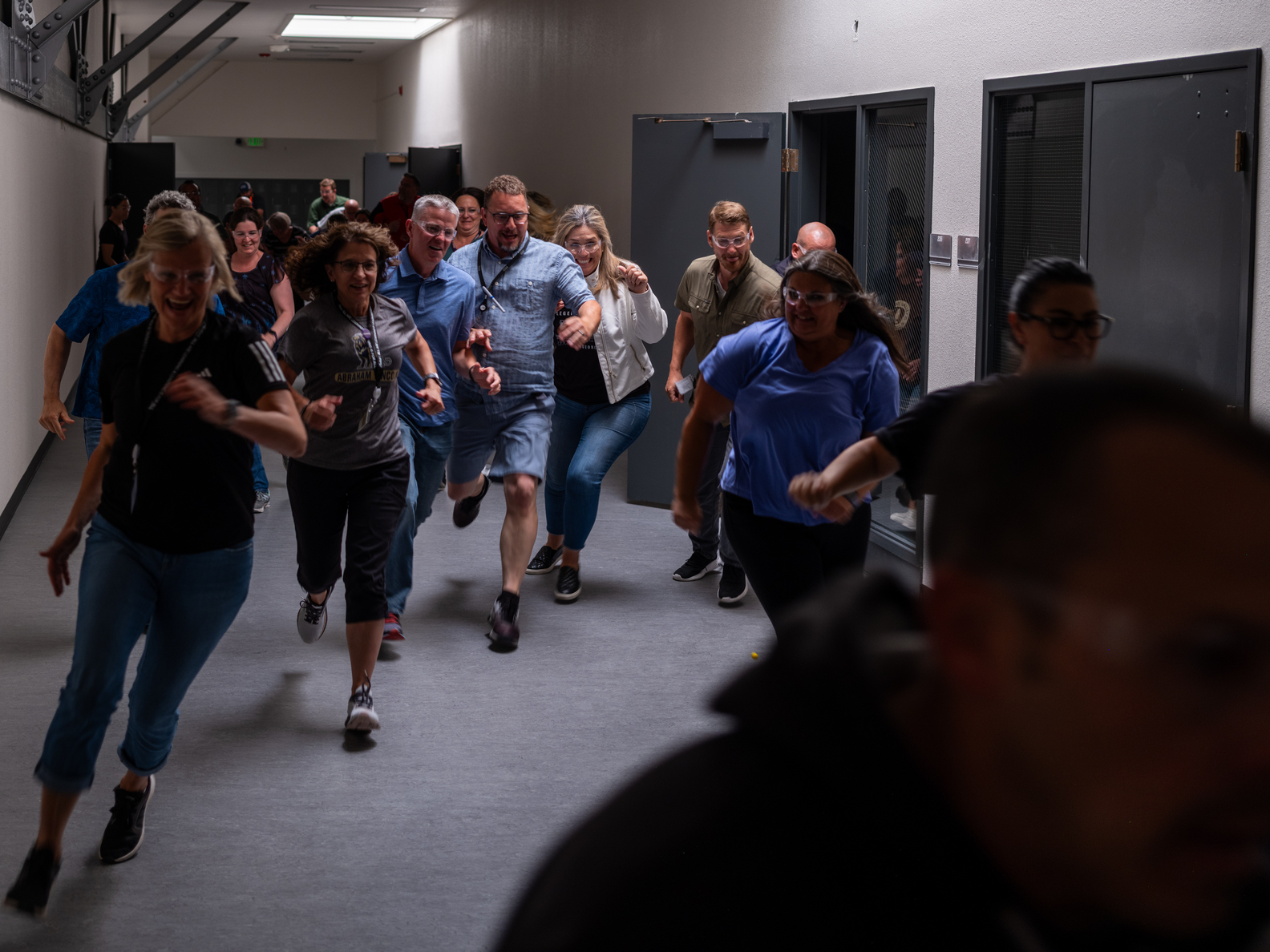

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

The face, reconsidered

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews