Alexis Haut|Interviews, The Design of Horror | The Horror of Design

November 6, 2025

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

From cults to connections, production designer Grace Yun reveals how she crafts the visual language of films like Hereditary and Past Lives—turning ordinary rooms into sites of fear, longing, and memory.

To see Hereditary is to be haunted by it.

Ari Aster’s 2018 psychological, occult horror film mixes shocking imagery with dysfunctional family dynamics — a combination that is as surreal as it is realistic.

Hereditary begins with the death of Ellen Taper Leigh (Kathleen Chalfant), the mother of Graham family matriarch, Annie. Despite periods of estrangement, Annie assumes her mother’s care in the last years of her life. Ellen takes her last breath in a bedroom in the Graham house, which Annie leaves locked and empty after her death.

Following her mother’s death, Annie (a terrifying Toni Collette) becomes increasingly unhinged. She obsesses over her work — a series of miniature replicas of familiar places like her own home and the site of her mother’s wake. She also obsesses over the cryptic, progressively sinister secrets Ellen left behind.

Annie’s loosening grip on reality wreaks havoc on her family, which includes her unnerving daughter Charlie (Milly Shapiro), her aloof teen son, Peter (Alex Wolff), and her increasingly bewildered husband, Steve Graham (Gabriel Byrne). As the film progresses and tragedies befall the family, the viewer begins to question if the Grahams’ madness is self-inflicted or the result of some inescapable fate.

I mean, who hasn’t wondered this about their own family?

Hereditary is filled with indelible images that make its darkly relatable themes vivid and unforgettable, no matter how many times you may try to exfoliate them from your brain with a silly sitcom or an emergency therapy session. You’ll never look at a diorama, a pile of walnuts or a the same again after seeing this movie. I promise.

A film that packs its horrific punch into its unique visuals relies on the vision and execution of its art department. And a film that needs an upper-middle class home in the middle of the Utah pines to transform into an absolute hell house relies on an imaginative and gutsy production designer. Luckily, Ari Aster had Grace Yun.

Yun began to consider film as an avenue for design while taking a digital video-audio class at Parsons.

“I was part of this pilot program called Integrated Design Curriculum where I studied multidisciplinary mediums of art and design,” Yun says. “I realized [film] was a medium where I could incorporate all of my interests.”

After graduation, she hustled her way into film through a typical route, as a production assistant and intern in New York’s indie scene. Somewhere along the way, a design star was born. After working on a few commercial projects, Yun was brought on to design Paul Schrader’s 2016 film Dog Eat Dog, starring Nicholas Cage. She teamed up with Schrader again in 2017 for his Ethan Hawke-helmed thriller First Reformed, before working with Aster on Hereditary. Since 2018, Yun has worked with some of the buzziest filmmakers working today. She designed the production of Celine Song’s Past Lives, Ramy Youssef’s eponymous comedy-drama series Ramy, and Beef, Netflix’s award-winning limited series that explores the chaotic aftermath of a road rage encounter.

Yun sat down with Design Observer’s Alexis Haut in the midst of International Production Design Week, a global celebration of the under celebrated art of production design. During IPDW, Yun reflected on her work on Past Lives and Hereditary during screenings of the two films at The Metrograph theater in New York.

She traces her path from horror novice to the set of one of the genre’s buzziest films. She also shares why Past Lives is actually a ghost story, how she designed house that held Annie Graham’s hauntings at every size, and which part of Aster’s script rattled her so badly, she had to get up and take a walk.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity. It also includes some spoilers for Hereditary.

Production design is a collaborative art

Alexis Haut: Is production design a “learn on the job” type of profession?

Grace Yun: Oh, totally. I felt my training was very much baptism by fire. I was thrown into the mix. It was like, hey, we don’t have a prop master. Why don’t you get thrown into it? And I’m like, what does a prop master do? What is a prop? I didn’t even know the answers to that. And I just had to figure it out. And the great thing is that you’re never alone in doing that. You have a team with you, hopefully a good team, good creative collaborators, and you do it together.

AH: Who are your biggest collaborators on set?

GY: The DP and the costume designer for sure, art directors, set decorators, really a lot of the heads of department. I’m getting more involved in and learning about post-production as well. Even with colorists, realizing how we’re the bookends of the film. I start with the color palette, they end with the color palette. And we normally don’t really communicate with each other, I find that kind of strange. So I think as I get invited to more color sessions, I’m realizing, oh, they are very thirsty for information during production in terms of our intention for certain colors or like if there’s a thematic thing happening with a certain shade. So I’m seeing, it would really benefit if we could have a conversation with each other.

AH: What do you think the production designer’s role is in bringing the film from script to screen?

GY: I like to see where design can play a role in propelling narrative, you know, if that’s appropriate. Not every project needs the design to be as expressive, sometimes it has just a supporting role, not a propelling role. But when a director wants to utilize design, that’s always exciting. I do think design can solve a lot of challenges and issues that might occur in the script — like a spatial issue or a blocking issue.

AH: Do you see it as its own form of storytelling?

GY: Oh for sure, yeah. I really think so. I think depending on a director’s approach, filmmaking at the barest sense is a succession of images held in a timeline. Some of those images don’t even have characters in them. The vignette or the mise en scène, it can say so much. It gives the audience a breath, it gives the characters a break. With just one little setup it can say so much.

AH: Hereditary is a film that relies heavily on design. Let’s go back to the beginning. How did the script get to you? What excited you about it?

GY: So I got this script from my agent at the time and I remember reading it and I remember thinking immediately off the bat, whoa this is ambitious! But it was so well written and it was so layered. It read like a Greek tragedy to me really. And more than just a horror script, I felt like there are these themes of grief and how Annie processes her grief can push her into hyperbolic states.

I was having a blast reading it and then I got to the point where Charlie gets decapitated and I was like, whoa. I took a break. I turned the lights on, I think I got something to drink and walked around. I was like, okay, okay, I’m all right. And then what I read afterwards, that Peter kept driving in a state of shock, I thought that was so brilliant. And I was like, I have to meet Ari. I just love the way he treated that moment and leaned into the shock of it. I met Ari and he’s the sweetest. most calm person. It was so interesting that this whole intricate story of horror and tragedy can emerge from this person. But we had a really wonderful, creative back and forth conversation. I think we closed down the cafe we were in and continued to walk and keep talking about the script. And that was I guess the beginning of it all.

AH: Was this your first time working on a horror movie?

GY: Yeah. And I, admittedly, was not a horror fan. I think because imagery will stay in my head for so long and I’m a bit of a scaredy cat, so I was unfamiliar with the genre itself. But Ari seemed really taken with that and he thought that was an asset more than a hindrance. And he was like, I really want to treat this story kind of like a drama and not lean into the visual tropes of the horror genre.

AH: That shows up in the film. Hereditary is so unique and the images are so unique. Did you give yourself a crash course on horror before you began?

GY: Prep on the movie happened very quickly after that meeting with Ari. I found myself in Utah with everyone and Ari hosted these movie nights. We would watch these reference movies and most of them were not straight horror. We watched Rosemary’s Baby, and the Mike Leigh movies. Then we watched 45 Years, it’s a beautifully dramatic movie, but he likened it to a ghost story. The couple, married for 45 years, becomes suddenly haunted by the husband’s previous relationship. It’s like the memory of her and the discovery of her and the existence of this previous relationship is haunting the entire household. I think it’s a really well done movie and if it wasn’t for Ari I don’t know if I would have had a chance to watch it. Focusing on the character and family dynamic heightened the stakes in the movie and I thought that was such an interesting approach to the genre.

Hereditary’s horror was built from the ground up

AH: Ultimately, Hereditary explores the horror of family trauma and family systems. It seems like getting the Graham’s house right was absolutely essential. Instead of using an existing location, you built it. Why?

GY: It’s funny, I think one of the first conversations Ari and I had was like, it would be great to build this. But due to our smaller budget level, producers wanted to location scout. And you know, I think we scouted for like a month, looking at various spaces and houses. And as we were doing that, we had these shot listing meetings where Ari would map out every single scene. He had an idea of how he wanted it to be shot. I would draw these layouts on a whiteboard and Ari would draw like a shot list map. And the more we scouted and the more we were in those meetings, we just were like, we’re never gonna find this house. That’s not possible, unless Ari significantly compromised his vision. So finally, we got a chance to build it, but it was very late in the prep process. It was a mad dash to design it, to build it. And also we had this other element, this key prop element, of the miniature of the Graham house that needed to be made based off of the set we were going to build. So just being able to coordinate and organize that and send all the information off to our miniatureist, that was our biggest challenge.

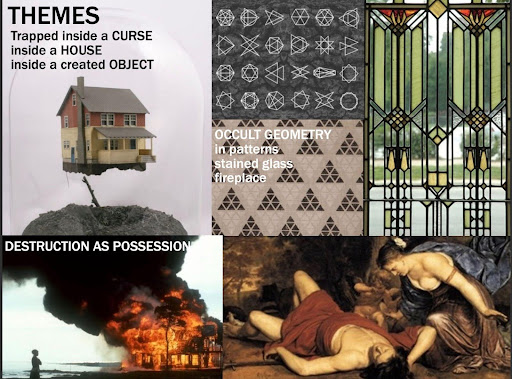

AH: Before I knew it was a build, I kept looking at the house like is this a real house?! Some of the details are just so uncanny, like the Wainscoting on the walls — it’s almost shoulder height — and the stained glass windows. What was your vision of the aesthetic of the house?

GY: There were scenes in the script where, especially the scene in Peter’s bedroom, where there is this meshing of worlds. Like yes, there is the real life sized Peter bedroom and the miniature of Peter’s bedroom in the shot. And I thought about taking that concept and applying it to the Graham House as a whole, as if they were figures in Annie’s artwork. The characters are trapped in her psychosis in some ways, and so I researched dollhouses and saw that usually they’re very intricately textured and colorful. So we really embraced that.

I also had a lot of fun with putting in the details and the patterns from the research that I was doing about occult imagery and sacred geometry. For instance, you noticed that the Wainscoting is up at the shoulder, I knew that there were some shots where they’re walking down that long hallway on the second floor and there’s a tracking shot where it’s tracking with a character from the side. I wanted this line to hit at the head as a kind of call back to the decapitation because that’s quite a theme in the film. And also it creates this feeling that the characters are buried in the ground.

There’s one of Annie’s artworks of a miniature, it’s right by the staircase, and it’s stacked with different houses from different eras that are buried in soil. It shows the concept of many generations and layers of trauma and tragedy being compounded and also many generations of this occult workings that Annie’s mother was orchestrating. So this is like the culmination of this whole other storyline that’s happening that we don’t really see until it comes to its apex. We were trying to embed those themes into the textures of the house.

AH: That’s brilliant, and it really does come across. From the exterior, this is a beautiful suburban, upper-middle class house. And then you go inside, and everything seems a little bit wrong. You use regular everyday objects in a really terrifying way, like space heaters and cutting boards. Do you think that domestic spaces and objects have unique potential to be especially horrific?

GY: Oh yeah. I think one of the themes that Ari and I would talk about a lot is like how mundane life could be horrific. Anything can change the spirit that imbues and embeds objects, and they can embed any kind of object really and I think that’s what’s so scary about it. I liken it to the sensation of when I witness something scary or horrific or I watch a horror movie, and then I come home. Everything seems a little bit sinister. I think it’s Annie’s psychological state that is making things terrifying. But she’s not wrong, you know, it’s not only in her head, it’s actually happening. We really wanted to convey and and loved playing with, you know, that something ordinary can be evil.

AH: What had to be true, practically, to get the different shots Ari wanted?

GY: Well luckily Ari had a lot of these shots planned before we were building it. So we were able to build in these wheeled walls so we can separate it from an entire side of the room. They mimic how a dollhouse can open up. The entire facade was able to open up in order for certain camera moves to happen. Also, for the A-frames of the treehouse and Charlie’s room I was leaning on the triangle shapes that are common in occult imagery.

AH: I found the exterior sort of uncanny as well. Admittedly, I don’t know that much about Utah and its topography, but one moment the characters are in the midst of a thicket of trees and the next they’re in a wide open space; it’s a disorienting landscape. Why did the team choose these exteriors?

GY: Utah has such a gorgeous, varied landscape,it was just amazing. The Graham House, we wanted it to feel quite remote and enclosed. There isn’t much society nearby. And then those vast long expanses also wanted to feel like the characters are these tiny figures in this vast landscape. They’re separated. So there’s this feeling that they’re kind of helpless and alone.

Sweating the small stuff

AH: Hereditary is also a movie that relies heavily on props, specifically Charlie’s objects and the seance materials. How did you collaborate with the props master and the art department?

GY: We found a great fabricator, an artist and sculptor, Sam Demke. He took charge of all of Charlie’s figurines and artwork. I really love the parallel of Annie and Charlie both having this artistic practice. And for Charlie, she was using found objects to create something creepy and sinister, but it had to seem like something Charlie didn’t find sinister or creepy. It was something that she was just interested in. So it had to really ride that line. In fact, with Sam, there were times where it almost went a little too far, too creepy, and then times where it went a little too cute. It took several rounds to just nail it.

AH: You already mentioned the miniatures. I know you worked with a miniaturist, Steve Newburn. That seems like such a complicated and interesting process to be designing both the set and the miniatures. How did that all work?

GY: I mean it was difficult because their studio was in Canada. Setting up a file share system was paramount. Ari wanted to show that Annie was a working artist and that she had multiple miniatures already and each miniature represented an event in her life. She was recreating the environment and the event that happened in that environment.

Some things the audience sees in the film itself, like the funeral home, then Charlie’s decapitation site and the Graham House. And then there were some others that were just kind of made up. Some were a little more straightforward, like okay, here’s a kindergarten, here’s a reference for a kindergarten, let’s do that. As we were building her workshop, we had to figure out the scale of each one and like how much room was gonna take place and how we can maneuver that and the quantity that Ari wanted to see. So that was a bit of a puzzle to figure out. But in the end, when we got close to shooting the specific elements of the miniature, that team flew in from Canada. Once they were on the ground with us in Utah, things became much easier because they could walk through the physical set. They kept working down to the wire, till we started shooting. It was amazing.

People like a good haunting, evidently

AH: People continue to watch and rewatch Hereditary. Here’s a recent Letterboxd review that I think encapsulates how many fans feel about the film. Andre de Nervaux wrote: “I’ve never been so terrified in my life. My favourite film of the fucking year.”

GY: Laughs

AH: I’m wondering from your perspective as someone who worked on the film, why do you think people feel this way about it?

GY: Oh, I don’t know! I think I knew when we were making it, we all were like, oh, this is really crazy. It was really layered. Everyone was so dedicated to it. And Ari’s vision was so huge. It was certainly an ambitious project. I don’t know how it resonates with other people, but I know how it resonated with me. I saw it as a Greek tragedy in that the family and the characters are so layered and the family dynamic is so melodramatic and gripping.

There are also unexpected moments of humor, which I love too. And I think because that is so strong in Ari’s writing and his direction, like the horror stuff almost becomes more potent. It packs more of a punch in a way because like the characters are really fully flushed out. And they have backstories. I remember at one point during prep, I asked Ari like, hey, do you have any character backgrounds, just like a quick little summary. He sent me this whole packet of information on every character. And I was like, this could be a prequel. There’s so much information about these characters. And I think because he knew them so well, it shows itself in the acting and in the writing. Ari told me his favorite type of designs in movies is when you re-watch it and discover more meaning behind it and more things behind it. So we tried our best to add in the layers to reflect the depth of the characters and the narrative. I think that it was impactful to me in that way. For others, I’m not quite sure.

AH: I think you’re exactly right. To some extent most people can relate to some of the aspects of this family, whether we like to admit it or not. And then, when you add this horrific element to it, it is much more potent. I think for some people, it’s cathartic to see those dynamics represented on screen.

But I am also curious about your work on Past Lives because it’s not a horror movie, but in a sense it is a haunting. Nora (played by Greta Lee) is very haunted by a past and a life she could have had. From a design point of view, I was really struck by how bare her and her American husband Arthur’s (played by John Magaro) apartment was.

GY: When we were developing the color palettes for the character spaces, Celine showed me a photograph of her old apartment in the Lower East Side. It was quite minimal and spare and I kind of took that as a cue for Nora. I wanted it to feel in the colder spectrum of colors — lots of grays and and blue tones — in comparison to Hae Sung’s world, which was a lot warmer and there’s these browns and wood textures and something that felt a little almost like a vintage quality.

You know, Nora is living her contemporary life. She’s a character that has ambition and a character who feels like she needs to step away from her past in order to really manifest herself. Where Hae Sung (Teo Yoo) is representing a culture that is also much older than American culture as well as something that is tied to Nora’s past. So I kind of wanted a little bit of vintage, warmer, hazier quality to everything in Hae Sung’s world. I think your observation that it feels almost like a ghost story, is true in the sense that there’s this whole other unseen spiritual aspect in that movie where there are connections, the inyun, there are thousands and thousands of years of connections that happen between spirits. And we wanted that to take up space and give room to it. So I didn’t want to overly clutter the sets. It’s almost like the negative space gives room for that spiritual space.

AH: The locations you scouted in Seoul and New York mirror each other. There are bars, parks, skyline shots and public art in both cities. What was your approach to scouting in two countries across the world from each other and finding locations that were similar but also not?

GY: Setting up these visual parallels was very important to us because we’re tracking these two lives that are running somewhat parallel to each other and then they intersect at certain points. And that feeling was quite important to capture and also the feeling of when they’re closer to each other, like let’s say during the Skype sequence, we really wanted to emphasize the time of day in each of their spaces. Seoul is literally 13 hours ahead. So, you know, if it’s daytime there, it’s nighttime here, vice versa, and there are a few times during the day where sunrise and sunset are within the same space. I think being able to visually create the parallels and then also create a feeling of distance and connection at the same time was definitely the goal. And that was something we were looking out for while scouting.

AH: What’s next for you?

GY: Right now I’m really enjoying time off and being a lady of leisure. I love having some time to myself. It’s really like I go into hibernation mode. And also being home in New York, a lot of my past projects have been everywhere else, so just being home in New York has been really nice. So, I don’t really know what’s next. I usually come out of these like rest periods just with an urge to do something somewhat specific. It’s like the mood is specific or something. You know, I remember when I got Ramy, I was like, I really want to do something about spirituality and identity crisis. And then when I got Past Lives, I wanted to do something that felt a bit more romantic. So maybe if the universe continues to be kind to me, something will manifest and show up.

AH: And it’s nice to have that time to figure out what it is you actually want to be working on. Is there anything I didn’t ask you or that you didn’t get a chance to say?

GY: I don’t know if I have anything particularly insightful about this, but there’s a lot of murmurings about the shift of our industry and of how we’re making movies. And I think the landscape will definitely change, but I don’t think it will be completely replaced. I don’t think human stories can be completely replaced. Even in the next generations, I think there’ll still be stories to tell. And even if it’s thematically similar, I think the presentation of it will be different. The expression of it will be new and different and fresh. People get tired of the formula, people get tired of the spectacle. Formula and spectacle are great when you want a little snack of a story. But I think the best stories help us understand our own experiences and what we’re going through. And I think there will be experiences that feel quite unique to us, so I need a group of good human beings to help me through them.

More like this:

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison

Sing Sing is a movie that takes place in a prison, but it’s not a prison movie.

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

About face: ‘A Different Man’ makeup artist Mike Marino on transforming pretty boys and surfacing dualities

On the cusp of Oscar Sunday, we’re talking award-winning makeup that gets under the skin.

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Glamour enlivens heritage and history in Hulu’s genre-bending series about a Pakistani family running an international drug ring from Philly corner stores.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Alexis Haut

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

The face, reconsidered

Design Impact

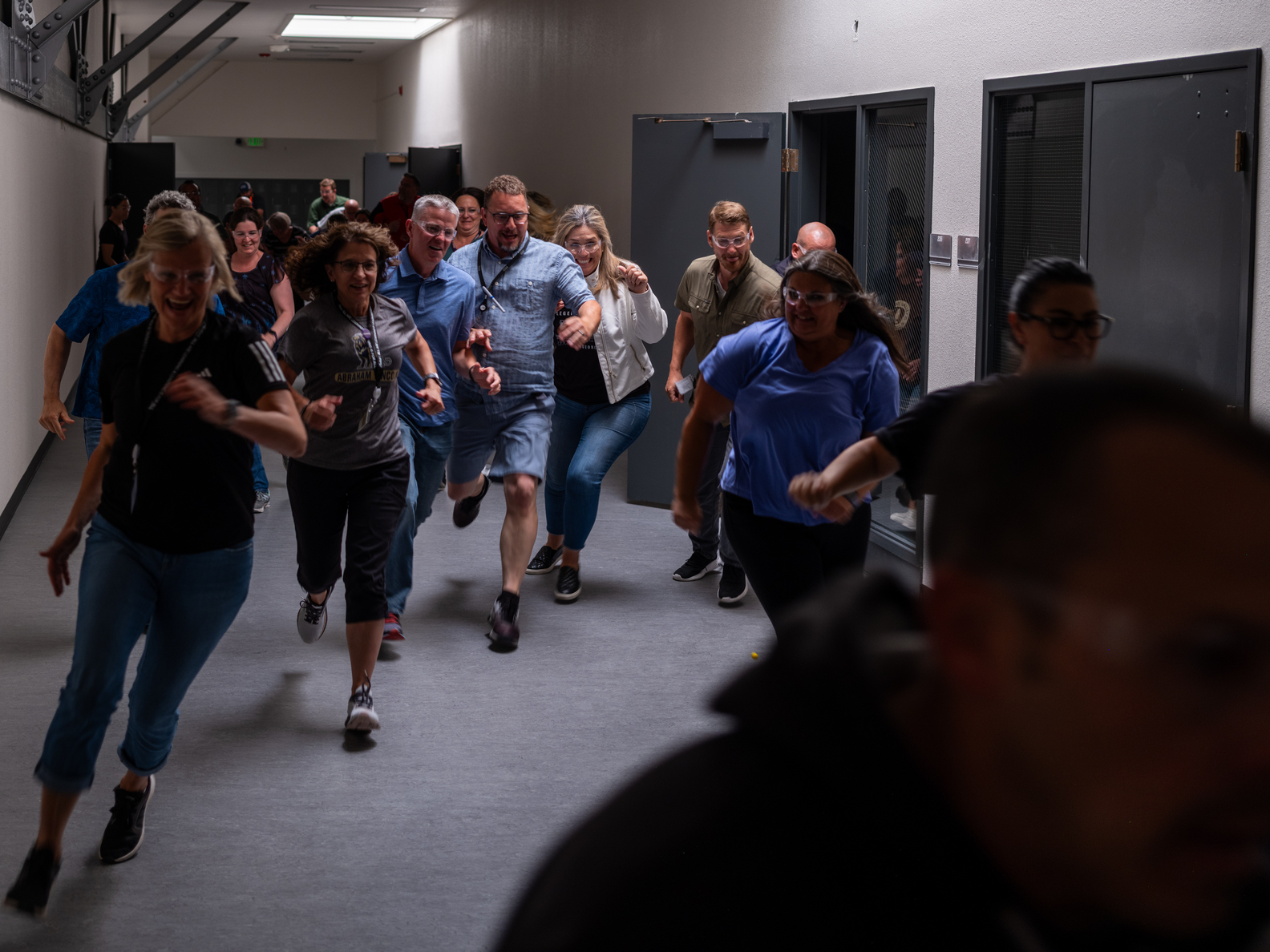

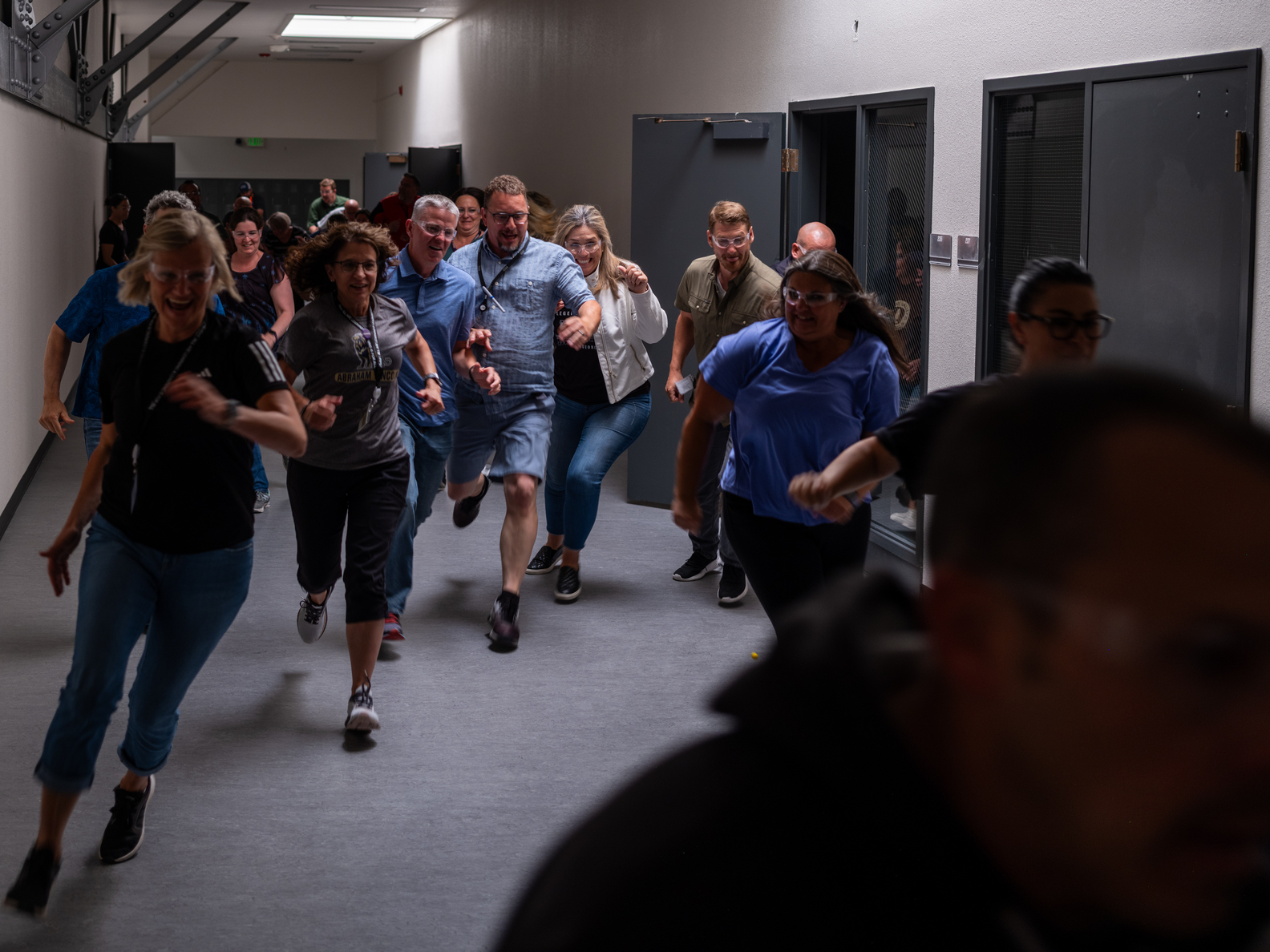

Alexis Haut|Education

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

The afterlife of souvenirs: what survives between culture and commerce?

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

The face, reconsidered

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

Alexis Haut is an audio producer, writer and educator based in Brooklyn. She spent seven years teaching, leading teachers and coaching basketball in middle schools in Brooklyn and Newark before independently producing her first podcast series in 2018. Her audio work includes the

Alexis Haut is an audio producer, writer and educator based in Brooklyn. She spent seven years teaching, leading teachers and coaching basketball in middle schools in Brooklyn and Newark before independently producing her first podcast series in 2018. Her audio work includes the