William Drenttel, Jessica Helfand|Essays

February 6, 2011

Introduction to Graphic Design II

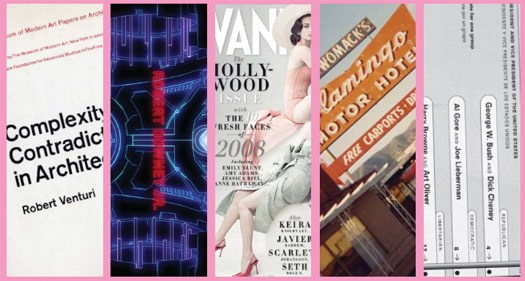

2. Opening titles for Iron Man, designed by Kyle Cooper, 2008

3. Cover, Vanity Fair, photo by Annie Leibovitz, March 2008

4. Flamingo Motor Hotel, photo by Rick Poynor, 1978

5. Sample Ballot, Design for Democracy by Marcia Lausen, 2007

This article, in an earlier version, first appeared in Dwell (December/January 2009, Vol. 09 Issue 02) in an editorial series of “introductions” to various aspects of design and architecture. The authors thank Dwell for its original publication in their pages.

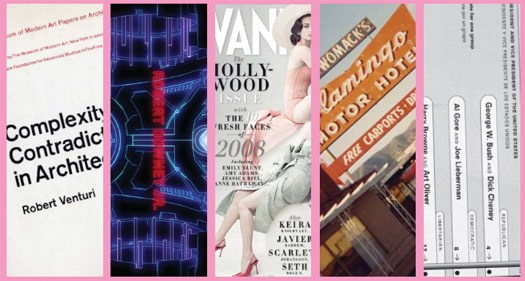

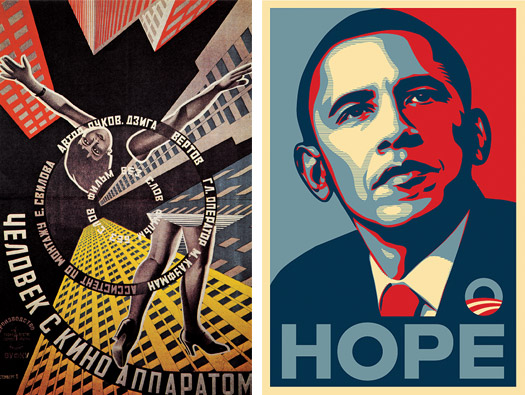

Broadly defined, graphic designers (sometimes referred to as “communication designers”) are the visual ambassadors of ideas: their role is to translate, communicate — and occasionally even agitate — by rendering thinking as form, process and

In addition to their role in the visual engineering of most printed matter, graphic designers today lend their expertise to a host of related disciplines including, but not limited to, strategy and consulting, information and experience design, branding and broadcast design and signage and wayfinding systems. They are groomed to acquire a certain classic set of skills (which today demand a facility with software) including drawing, photography, composition and typography — the design and structural characteristics of letterforms, arguably graphic design’s lingua franca.

Isotype Pictograms: Isotype — an acronym for the International System of Typographic Picture Education — was developed after World War I by the Austrian educator Otto Neurath. With German illustrator, Gerd Arntz, Neurath created a hieroglyphic vocabulary of easily understood symbols that have been assimilated internationally.

I Love NY Logo: Designed by the grandfather of graphic design, Milton Glaser, in the 1970s, this rebus combines a red heart with the rounded slab-serif typeface American Typewriter.

UPS Pictograph: The UPS logo was designed in 1961 by Paul Rand as a sort of heraldic pictogram. Rand said he gauged his success when he showed the work to his daughter. (“Why, it looks just like a present, Daddy,” she said.) The logo was redesigned in 2003 by design firm Futurebrand.

Graphic Design Done Right: A good identity is simple, but never boring; flexible, but never chaotic; playful and iterative — and always supremely recognizable. Good examples of graphic design done right are Saks Fifth Avenue and The New York Times online.

A leading designer explains and describes “design thinking” as a methodology for design practices and organizations. An interview with Tim Brown was published on Observer Media.

Graphic Design: A New History by Stephen J. Eskilson

A substantial new history of graphic design, now being widely taught. Critically reviewed on Design Observer by Alice Twemlow and Lorraine Wild.

Graphic Design History: A Critical Guide by Johanna Drucker and Emily McVarish

Another new history of graphic design, also being widely taught. Critically reviewed on Design Observer by Denise Gonzales Crisp and Rick Poynor.

A contemporary take on design identities, branding, social networks, and national identities and borders.

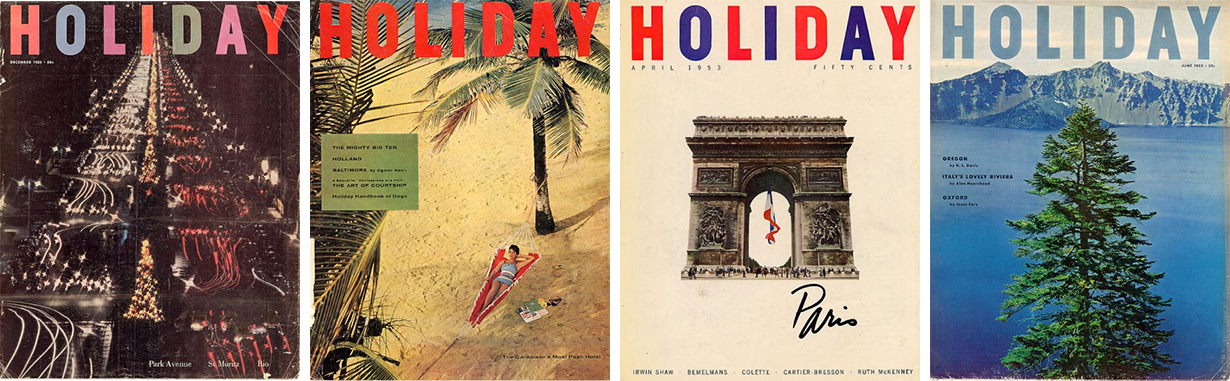

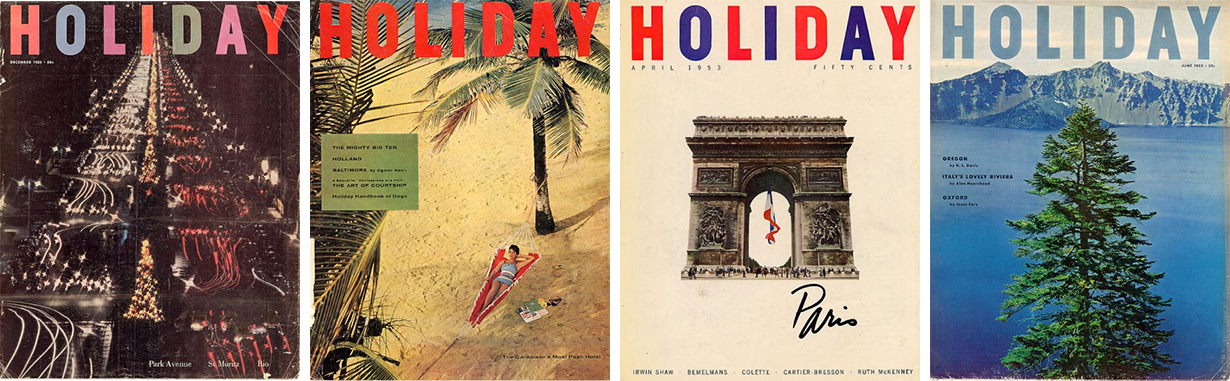

Merz to Emigre and Beyond: Avant-Garde Magazine Design of the Twentieth Century by Steven Heller

The head of Rotman School of Management looks at “design thinking” from the perspective of business innovation, as well as sourcing a foundation for this work in American pragmatic philosophy.

Observed

View all

Observed

By William Drenttel & Jessica Helfand

Related Posts

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

The Design Observer annual gift guide!

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Gratitude? HARD PASS

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

Recent Posts

The Design Observer annual gift guide! ‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison ‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change Gratitude? HARD PASSRelated Posts

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

The Design Observer annual gift guide!

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Gratitude? HARD PASS

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.