Prachi Khandekar|British Telecom, Essays

December 7, 2011

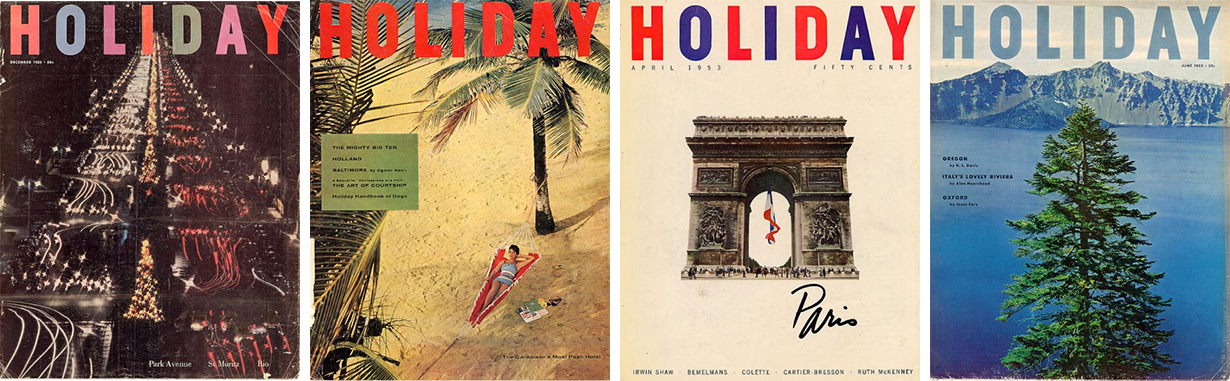

[MB][BT] Scripting The Future Of Telephony

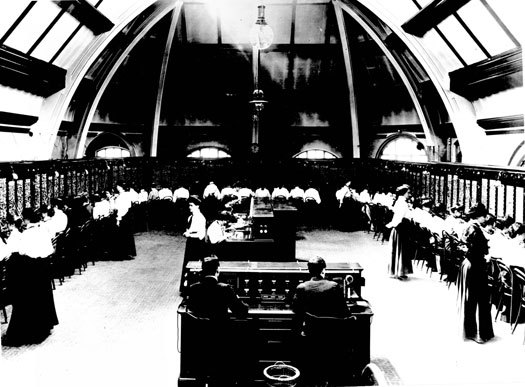

Image TCB 473/P 1026 courtesy of BT Archives.

BT is the world’s oldest communications company, with a direct line of descent from the first commercial telecommunications undertaking anywhere. The below essay is one of seven, the result of a collaboration with Teal Triggs and Brigitte Lardinois from the University of the Arts London and their students in the Design Writing Criticism program.

BT Archive retains the history of telephony in the form of crystallized moments. It houses a scrupulous assortment of images, utterances and objects that are waiting to recount forgotten stories. I was drawn to how each artifact was laden with history, and felt my new Sony Ericsson dwarf in the palm of my hand from being faced with its own ancestry. Then, as if to reinstate attention onto itself, it started ringing. I answered: Hello?

I don’t recall much of the conversation; I had stopped listening at hello. For the first time this automatic response had caught my attention. There are indeed countless codes of conversation that we unknowingly follow while using the telephone. But how did such codes develop? The archive helped me piece together a tale about the codification of language for the purpose of telecommunication. My research revealed an imperceptible service design strategy put in place to popularize the telephone. I discovered that the formalized training given to operators in the early days granted the telephone the indispensable status it enjoys today.

On the 6th of September 1879, the first telephone exchange office was inaugurated in London. There was an avid reluctance to embrace the telephone at the time and hence, the office was able to recruit only ten subscribers. Infact, in the early days, this new invention was not even regarded as a serious threat to the telegraph! It was only with the opening of one more exchange office in Birmingham later that year, that the enterprise started amassing some attention. Still, the founder of the Birmingham office, Henry Piercy, found it difficult to secure support from investors and was forced to offer 3-month free trials and discount rental fees for this expensive asset. Initially, Piercy employed just one male telephonist to operate the switchboard. However, from then on, the demand for telephone operators and, consequentially, telephones began a steep ascent.

I believe that the eventual spread of telephony from the business to the domestic realm can be attributed to the service offered by telephone operators. Information entropy, as defined by the Shannon and Weaver Model of Communication, is always a factor when it comes to the telephone. The prospect of losing information was a serious threat to the rooting of this form of communication, as people were already weary of its benefits. Therefore, fashioning a seamless experience over this feeble medium became an urgent task, setting the stage for a fastidious service design solution.

According to Nicola Morelli (2009), service design is aimed at improving client experience by boosting quality and facilitating interaction between the service provider and client. This inevitably translates to formalized scripts prepared for actors engaged in the service, to ensure maximum flexibility for the subscriber. I believe that it was to this end that language over the phone line was formalized during the advent of telecommunication.

I discovered various documents that evidence a deliberate attempt to standardize the language of telephone operators dating back to the early 1900s. The language used by operators was painstakingly defined through exchanges between officials at various General Post Office (GPO) locations. There was no particular method — most of the formalization took place as a direct response to customer complaints, reported either directly or in local newspapers. Slowly, the officials began to chisel away the confusing bits from the exchanges over the telephone to arrive at a tweaked version of the spoken language. This resultant language was designed specifically for the telephone. For instance, by 1923, a guide was released for the correct enunciation of numbers. This then became protocol and had to be followed uniformly by telephone operators throughout England. It’s interesting to see that wherever needed, the instructions consciously morph the everyday pronunciation of numbers to arrive at a distinct sound.

An examination of the exchanges between GPO officials elucidates the tedium involved in coming to a consensus about such codes. One example of this are the nuanced discussions that took place in the year 1909 to resolve the phonetic similarity between the number ‘0‘ (oh) and ‘4’ (four). Misunderstandings arising from the similarity, prompted Mr Preston, the General Manager of the Southern GPO, to write a string of correspondences. He wanted to see if other exchange offices had experienced similar problems and how the GPO might arrive at an apt solution. I unearthed a box of letters displaying the concerns from various parties and also found suggestions as to how errors could be circumvented. One officer pointed out that ‘0’ could be referred to as ‘naught’ but another officer responded promptly to point out that ‘naught’ could easily be confused with ‘eight’ if this was implemented. The discussion ensued for weeks with no resolution. Although the example didn’t amount to a revision of the script, it was crucial to my understanding of the vigorous consideration given to tweaking the user experience through standardized language.

The method of recording correct names and addresses also followed a stringent structure. The telephonists were asked to memorize the Standard Letter Analogy chart and were tested regularly to ensure adherence to the code. In addition to this, tightly defined guidelines instructed operators on how to connect a subscriber to the destination. While conversing, an operator was to consult and follow the script even when the response was obvious. There was no room for improvisation or casual demeanour. The aim was to deliver excellent and consistent service to the customer every time. If, as it often happened, there were technical difficulties, the telephonists were instructed to duly apologize and offer assistance to the frustrated subscriber in the most patient manner.

The Archive continued to satiate my curiosity for hours while opening up new doors. By learning about the standardization of language as an aspect of service design, I was able to situate myself as a participant in the long history of telephony. Though the times of operators and standard expressions are obsolete, I take pleasure in knowing that these important considerations continue to exist in an inert form, waiting to be discovered. In BT Archive one has only to follow a vague curiosity to unravel an unforgotten tale from the past.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Prachi Khandekar