January 30, 2018

Speech, Speech

Editor’s Note: This essay was originally published in January, 2007, but it seems especially relevant today, as we wait for Donald Trump’s first State of the Union address.

Does this sound familiar?

Your client has a message to communicate: an argument, a sales pitch, a call to action. Your job is to give it form. You’re an expert at this. You know how to take a complicated bunch of ideas and reduce them to their arresting, memorable, engaging essence. You come up with some big ideas that you’re convinced will work and, detail by careful detail, you bring those ideas to life. But there’s a problem: your work is second-guessed by a bunch of middle managers, some of whom are insecure, some of whom have their own agendas to inject, some of whom just like to say no. Despite all that, you refine and revise, hoping to keep the strength of your original idea intact. Finally, your work is approved, and it goes out into the world. If you’re lucky, it really makes a difference: minds are changed, passions are fueled, your client looks great. And, somehow, hardly anyone out there knows you were involved at all.

It sounds a lot like graphic design, doesn’t it? But I’m talking about something else: speechwriting. To a surprising degree, the two professions are remarkably similar.

My introduction to the world of speechwriting came through an unlikely (for kneejerk liberal me) source: Peggy Noonan’s 1990 book What I Saw at the Revolution, her account of working as a White House speechwriter for Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. At the end of her tour of duty, she was associated with some of Bush Senior’s most parodied lines, “a thousand points of light” and “read my lips: no new taxes;” today she’s a ubiquitous Republican pundit.

But in 1984 Noonan was still not far from her scrappy Irish-Catholic working class roots, working her way up the White House ranks, taking on small assignments and looking for her big break. That came five months into her job when she was asked to write a speech that Reagan was scheduled to deliver on the 40th anniversary of D-Day, before the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc at Normandy. It was a plum assignment. In one of the best parts of her book, she describes how she constructed the speech, building one vivid bit of description on another: if you’re a designer, you’ll recognize the pure pride of craftsmanship when you hear it. Amidst a lot of useless advice (“We want something like the Gettysburg Address,” more than one nervous staffer told her), a fellow writer kept telling her to remember something: they’ll be there. Noonan realized that he meant the aging Rangers who scaled the cliffs on D-Day, and not scattered throughout the crowd, but sitting together in the front row, just five feet from the president. It was a crucial insight, and from it Noonan derived the climax of the speech:

Forty years ago as I speak, they were fighting to hold these cliffs, Reagan said that day. They had radioed back and asked for reinforcements and the were told: There aren’t any. But they did not give up. It was not in them to give up. They would not be turned back: they held the cliffs.

Two hundred twenty-five came here. After a day of fighting only ninety could still bear arms.

Behind me is a memorial that symbolizes the Ranger daggers that were thrust into the top of these cliffs. And before me are the men who put them there.

These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped to end a war.

I don’t care what you think about Reagan, Noonan, Republicans, or the military-industrial complex: that’s a speech.

It made Noonan famous around the White House. She became “the girl who does the poetry.” She got more important speeches to write, and with them came more important people to oversee her work. The fun of the early small jobs were replaced by the tension of higher stakes. She began to “hate the comments, the additions and deletions and questions…sending a speech out…to be commented on by presidential aides, and their secretaries and their secretaries’ cousins.” Her frustrations will be familiar to you, as will her fantasy that one day the Top Guy will demand to know who’s been watering down his speeches, and demand “Get me Noonan.” Her dream client had gone bad.

She got an opportunity with one more speech, the one that consolidated her legend. On January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after takeoff, killing all seven astronauts aboard, one of whom was Christa McAuliffe, the first member of the Teacher in Space Project; because of her, many schoolchildren witnessed the disaster as it happened. Reagan was scheduled to give his State of the Union address that night. It was cancelled, and instead the president delivered a speech that Peggy Noonan wrote that afternoon; time was short, there was little time to review it and, hence, as Noonan says, “no time to make it bad.” It was short, extraordinarily moving, and ended with a quote from “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee:

The crew of the space shuttle Challenger honored us by the manner in which they lived their lives. We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them — this morning, as they prepared fro their journey, and waved good-bye, and “slipped the surly bonds of earth” to “touch the face of God.”

A deluge of mail and calls followed. But does it surprise you to learn that during the attenuated review process, someone from the National Security Council suggested that that the end be changed — quoting, of all things, a then-popular AT&T commercial — to “reach out and touch someone?” Noonan described this as “the worst edit I received in all my time at the White House.”

The Library of America has just released the landmark American Speeches, which collects, in two volumes, over one hundred speeches from Patrick Henry to Bill Clinton. But, as William Buckley, Jr., has pointed out, nothing is said about their genesis. We have to turn elsewhere to unravel the mystery of how much of JFK’s inaugural address (“Ask not what your country can do for you…”) was written by the president and how much by speechwriter Ted Sorenson; or to learn that the climax of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” was an improvised departure from the prepared script.

I’ve worked with many writers over the years. Some of my favorites have been former speechwriters. In my experience, they really know how to work with a designer. They know they have to fight for an audience’s attention; they know that what matters is not word count but persuasion; they know that words do not just provide information but reveal the essence of a person, or an organization. And they know to be appalled — but never surprised — when someone on the client end tries to ruin everything with a barrage of inept suggestions.

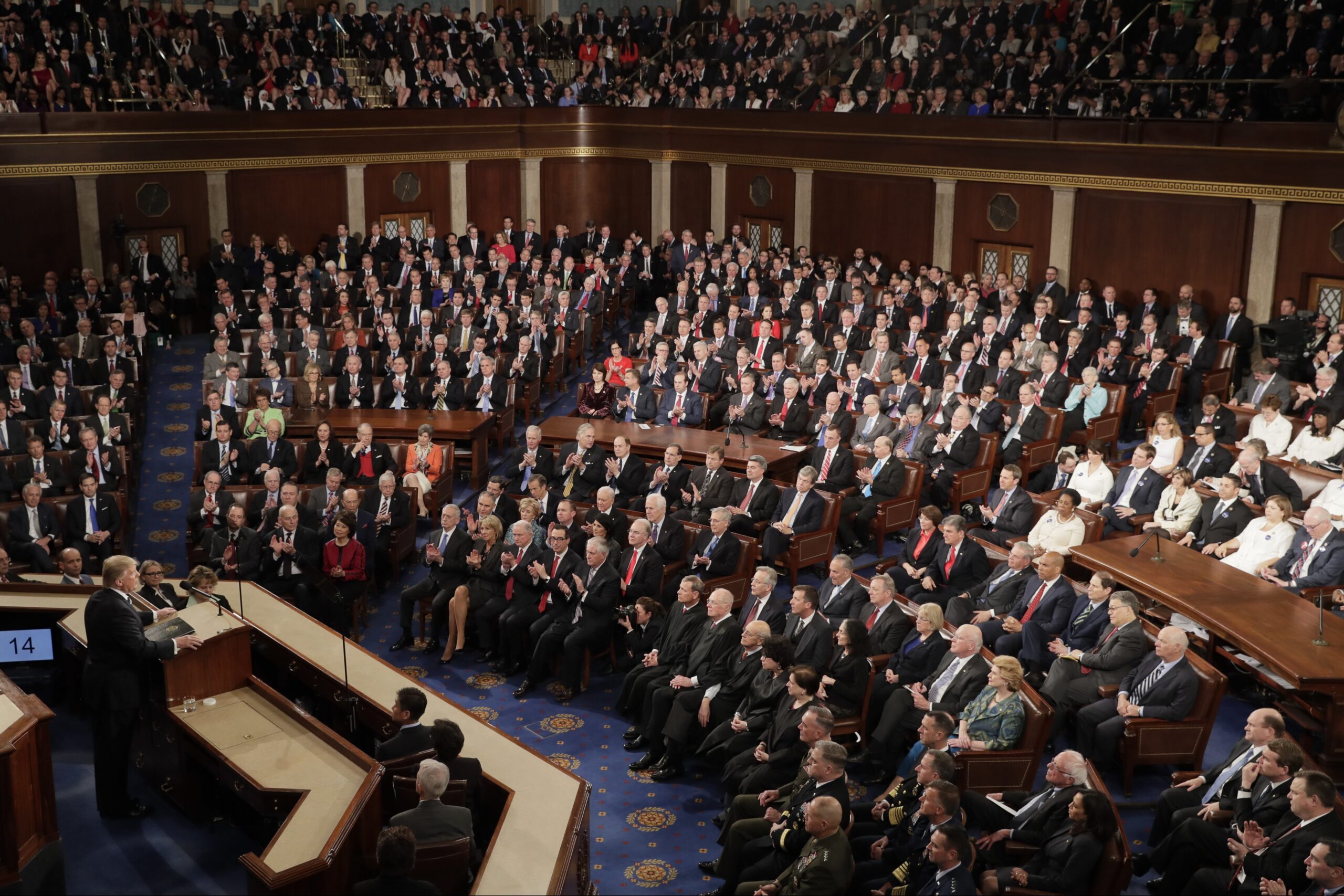

Tonight, George W. Bush — a man whom even his supporters would not hail as a great orator — will deliver his seventh State of Union Address. A small army of writers are busy trying to put together an address that will wipe out memories of Bush’s last outing, the less-than-persuasive unveiling of his latest plan for Iraq. “A mediocre speech that was flat,” speechwriter emeritus David Gergen told The New York Times. “It was solid, but they miss Gerson.” Gergen was referring to Michael J. Gerson who left the White House last summer. Gerson, according to the Times, is credited with Bush’s best speech, the one he delivered to the joint session of Congress nine days after the September 11 attacks.

It’s been a long time since George Bush has delivered a speech like that. But don’t blame his speechwriters. Maybe they’re working for a bad client.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Michael Bierut