Jessica Helfand|The Self-Reliance Project

May 8, 2020

Storytelling

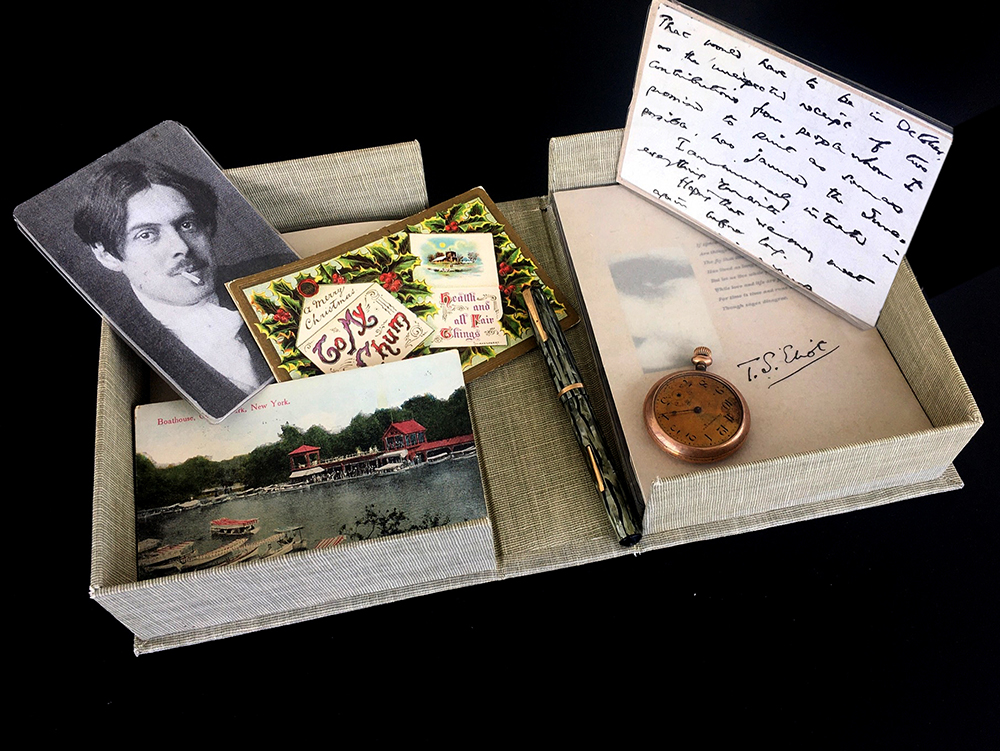

Jessica Helfand, In My End is My Beginning. Artist’s Book, 1989.

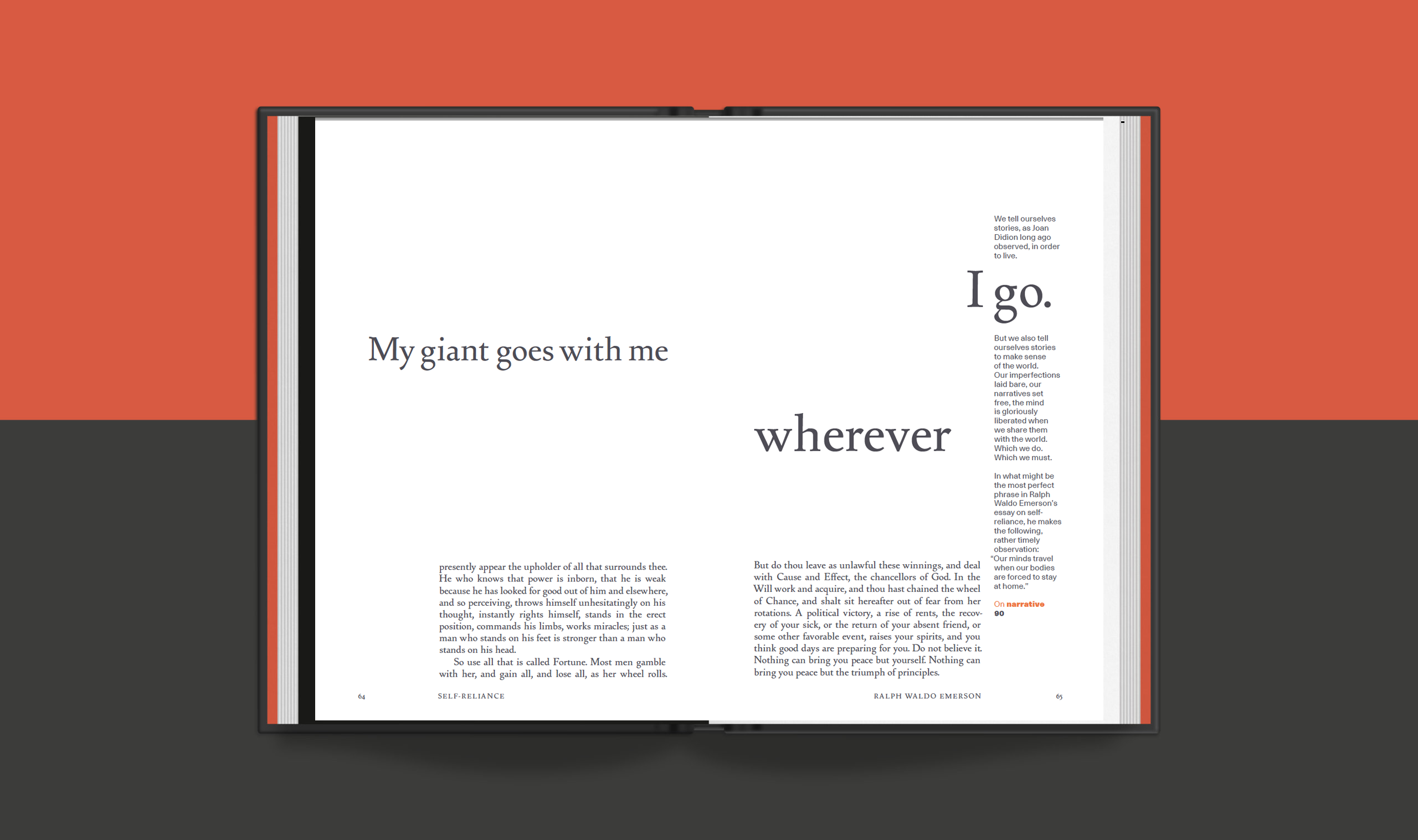

Emerson’s text is widely available to read online, but this new Volume edition—produced with Design Observer—elevates his wisdom through the printed word. With twelve essays from Jessica Helfand’s Self-Reliance Project: pledge now and order your copy today!

When I was in graduate school, I was obsessed with T.S. Eliot. I read everything he wrote, devoured any biography I could find, and for my thesis exhibition, made an artist’s book about him that consisted of a clamshell box filled with found materials, designed to look like they might have been his. The box encapsulated what I loved most about Eliot—his sadness and longing, his dark mind and haunted voice—but even more, it solidified what I loved about making things: the idea that you could immerse yourself in a story, and that if you were successful, other people could immerse themselves in it, too.

There’s something about combing through the flotsam of displaced evidence, about locating and recombining material fragments in new ways, something about those magical collisions of history and happenstance that’s almost choreographic. You’re thinking about space, and story; about character, and site; about mind and matter and more than anything else, about time.

That last part? Pure Eliot.

The artist’s book I made was an early, comparatively primitive attempt to make work that visualized someone’s life. And while my Eliot obsession lessened, that essential preoccupation with biography and narrative never left me. Writing. Teaching. Painting. Books. They’ve all let me experiment with telling stories, and perhaps more importantly, with telling time.

In my beginning is my end, wrote Eliot. In my end is my beginning.

And so it is. Our weeks of shapeless days have taken us across the solstice, from the monotones of winter into the multitudes of spring. These daily essays, cumulatively, now number more pages than Emerson’s original text. And so, it is a moment to pause: not quite an ending, but not quite a beginning, either.

Which may be the entire point.

We seek stories with beginnings and endings, craving the false reassurances of imagined closure. But narratives differ—wildly and ferociously—and we can neither anticipate nor control how they land for others. All of which explains their mystery.

And ours.

Joan Didion once said that we tell ourselves stories in order to live. But the way we tell them, and the way we digest the stories of others, that’s where the work begins: on ever page, in every syllable, and in every picture that is, as we all know, worth a thousand words.

But we also tell ourselves stories to make sense of the world. Our imperfections laid bare, our narratives set free, the mind is gloriously liberated when we share them with the world. Which we do. Which we must.

In what might be the most perfect phrase in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay on self-reliance, he makes the following rather timely observation.

Our minds travel when our bodies are forced to stay at home.

As we near the end of Captivity 1.0, we know that this was just a practice round. We have learned to be patient, to be still. We have come to tolerate ambiguity, and to embrace loneliness. But we also know that the mind is not as easily restricted, that the imagination can not so easily be caged. To be truly self-reliant is to trust in that deep well of possibility, of fierce individuality, of honesty—and of hope. In the end, as in the beginning, our stories are just our secrets waiting to be set free.

And for that, we have all the time in the world.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jessica Helfand

Recent Posts

Lessons in connoisseurship from the Golden Globes “Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAIRaphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.