November 5, 2018

Voting ≠Hoping

In the summer of 2010 I took Milton Glaser’s storied summer intensive. It was 80 hours of lectures and assignments—which Milton had refined for over 30 years—peppered with luminary speakers. All of it was squeezed into into five short days. During one of the lessons Milton rested his coffee on the table and filled a pause by looking at each of us. then he said, “please come forward and try to lift the cup.” The first few volunteers lifted it with ease, after which he calmly said “no.” Eventually someone caught on and performed the act of being unable to lift the cup, straining against the weight of an imaginary gravity. “Good,” he said. Then Milton pointed out that trying isn’t the same as doing.

Milton’s observation doesn’t feel true, after all “try” is a verb. Trying to acquire things, like jobs or romantic partners, requires taking action. We try our best and then twist into knots hoping for a reply. Trying can lead us to become consumed by hope. Feeling hopeful, this state of mind that’s supposed to be positive can in fact tear us apart. Milton’s observation doesn’t feel true because trying is an action, but he’s not wrong. Trying to lift a cup is an expression of hope about a possible future. Lifting a cup happens, and it happens where we actually are.

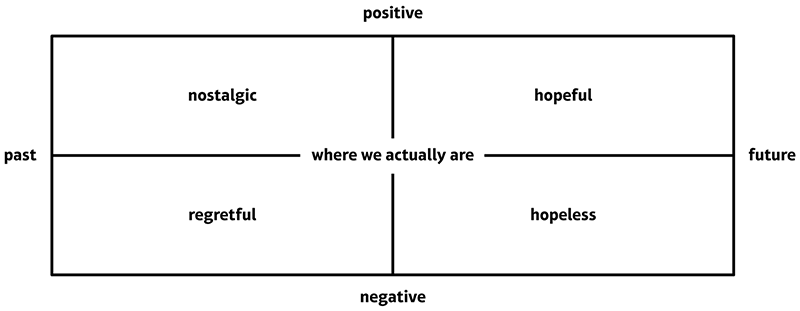

American politics would have us believe that hoping alone is capable of heavy lifting. Campaign slogans feign to hope us all into a brighter future but there’s always a subtext: the hope that we can beat them. Both political parties hope against each other with a sense of burning urgency that boils into rage—believe me I’m boiling—but some of this rage, like the impatience of hoping for a reply, bubbles out of the frustration of hope’s ineffectuality. Hopeful and hopeless are often framed as binary opposites at either end of a spectrum, but they’re in fact side-by-side. Both states of mind exist in an imagined future. Both states of mind are in effect a distraction. The real other end of this spectrum is nostalgia and regret, states of mind that exist in an imagined past. The center of the spectrum is where we actually are, and this is the place where the doing gets done.

Reading is a good allegory for the way doing happens—for the way progress unfolds. When we get lost in a book, we’re specifically, and perpetually, lost inside the page we’re on. We focus on the text at hand and the world dissolves—all of it—visions of the future and the past, the pages that came before, and the ones that follow. We press into the pages that lay open before us and end up racing forward as a result. Yes, we follow the text back and forth, down and across, but these movements go unnoticed from within the narrative. It doesn’t feel like we’re moving through the book, it feels like the story is moving through us.

The design process moves much like reading but it’s seldom presented that way. Instead design is packaged and sold as being future focused—a catalyst for innovation. Indeed, designers chart courses through the fog that connects the imaginary and the actual. We operate inside the way things come to be, and see this transformation in enough detail to know that hoping doesn’t get it done. Design, like reading, is a forward motion that comes from being focused on where you actually are. You may begin by hoping for a desired outcome but the best design outcomes result from correcting course in response to discoveries made along the way. Fixating on desired outcomes, or the steps in a prescribed process, can cause you to miss the discoveries when they happen—robbing you of the opportunity to react.

Design Thinking, as it’s packaged by IDEO and Stanford, has been criticized for not delivering on its promise—the idea of a set recipe for predictably innovative results. The truth is each design challenge requires not only its own unique design solution, it also requires its own unique design process. The particular needs of each design challenge uniquely warp preexisting design processes. In this way, at its best, design is the opposite of hope. There’s nothing speculative about it. Margins end, buttons are, even when it’s responsive text is wherever it is. Designing means moving actual things in the actual world—it means lifting the cup.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not suggesting we can stop ourselves from hoping. Our brains are organic prediction algorithms, and contrary to the position of many meditative disciplines, I don’t believe that we can turn that off entirely. Swinging back to politics, I desperately hope the Democrats retake both houses of congress on November sixth, I burn for it, I am in fact boiling with rage. Undoubtedly I’ll spend the evening of the election writhing in anticipation, hoping with every fiber of my being that we can correct course. Before they call the races I will be consumed by hope—it will tear me apart.

Since the last presidential election I’ve toggled back and forth between feeling hopeful and hopeless more times than can ever be counted. Obsessively imagining the future has made me weary. Maybe this essay is wishful thinking and nothing more. A yearning for the peace I find when I’m in the midst of designing something. At the very least I know I’ll find that peace inside the voting booth—alone with my ballot and my pen, standing where I actually am, moving actual things in the actual world.

Report voter suppression.

English: 866-OUR-VOTE

Spanish: 888-VE-Y-VOTA

Arabic: 844-YALLA-US

Asian/Pacific Languages: 888-API-VOTE

ASL: 301-818-VOTE

Observed

View all

Observed

By Brian LaRossa

Recent Posts

Announcing: Design As Season Two The Design Observer annual gift guide! ‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison ‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change