May 5, 2015

Exposure: Head below Wires by Roger Ballen

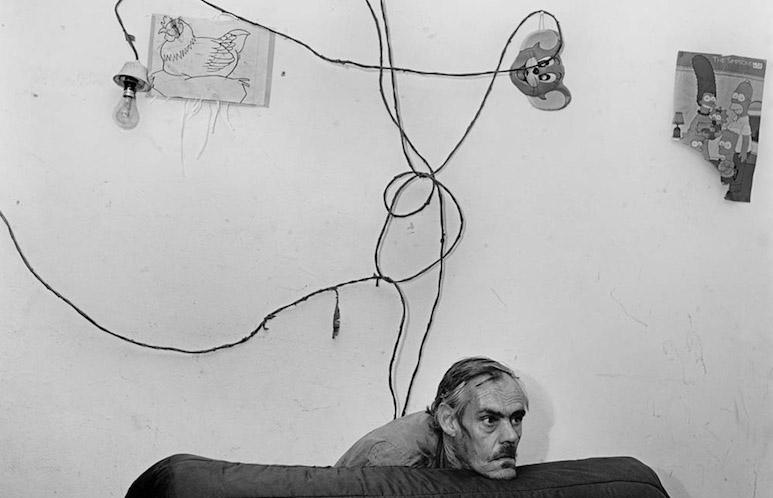

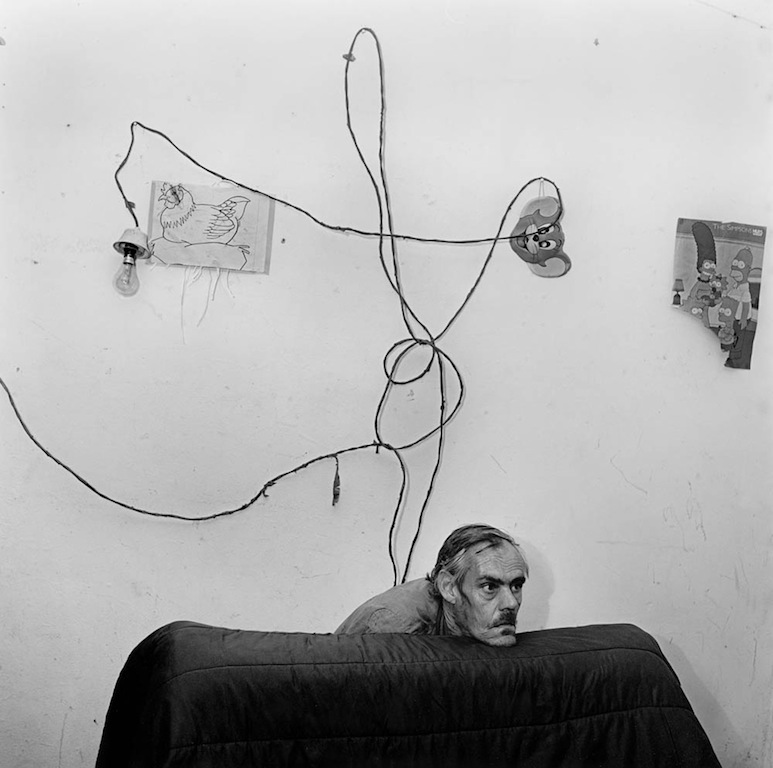

Head below Wires by Roger Ballen, 1999

Roger Ballen’s path has taken him from documentary pictures of people dwelling on the margins in small, neglected South African towns to staged installations where the art photographer’s subject, as Ballen readily acknowledges, has become his own state of mind. Head below Wires (1999) came at a point when this change in his photographic practice was already under way. It was published in 2001 in his book Outland, which has just been reissued in an expanded edition with more than 30 previously unpublished pictures.

Ballen cites the Theatre of the Absurd—a term coined in 1960 by the critic Martin Esslin—and in particular the plays of Samuel Beckett as early influences. As Esslin writes, this form of theater, “strives to express its sense of the senselessness of the human condition and the inadequacy of the rational approach by the open abandonment of rational devices and discursive thought.” Ballen’s protagonists and settings frequently resemble episodes from one of these theatrical productions. He likes to shoot the collaborations against a wall, as in this picture, heightening the impression of individuals pinioned within a severely restricted frame. Their actions may have no rational explanation—why does the man rest his chin on the couch so intently?—although they appear to convey states of psychological estrangement or existential unease.

In the subjective version of the outland invented by Ballen, animals often play an expressive role alongside the people, reflecting their domestic place in the lives of the impoverished participants. In this case, the usual birds and cats are represented by pictures that may or may not belong to the room’s occupant, and Jerry the cartoon mouse acquires a torn cartoon family. Sometimes Ballen encourages his sitters to draw on the wall and the absurd convolutions of the light fitting serve the same graphic purpose here. How these meager props relate to the man is left to the viewer to decide.

Some critics find Ballen’s images exploitative, though he is friendly with his subjects and the pictures couldn’t be staged without their enthusiastic cooperation. Exposure to the deprivation, squalor and mental instability of the outland is disquieting. Ballen’s images can be both alarming and impossible to look away from. “I see my photographs as mirrors, reflectors, connectors that challenge the mind,” he says. The pictures are not made in the safety of a studio, but in real places where the photographer must proceed with care. They cross territorial and mental thresholds far from the experience of many viewers and the danger is palpable.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rick Poynor

Related Posts

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

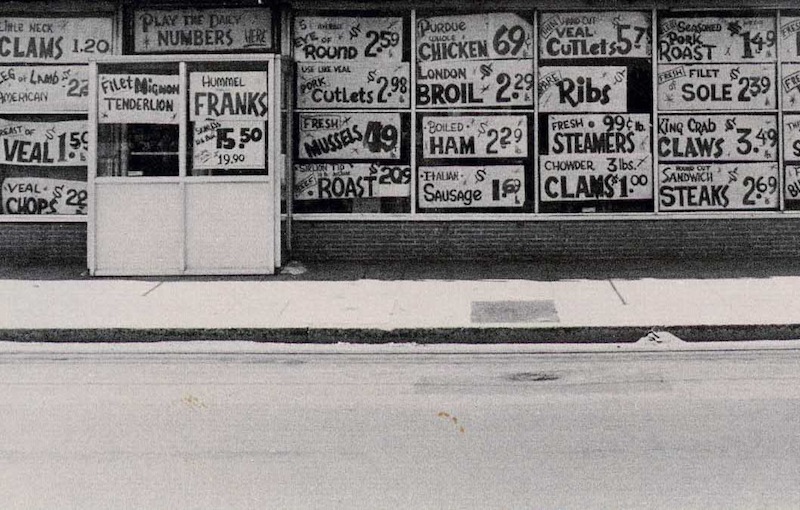

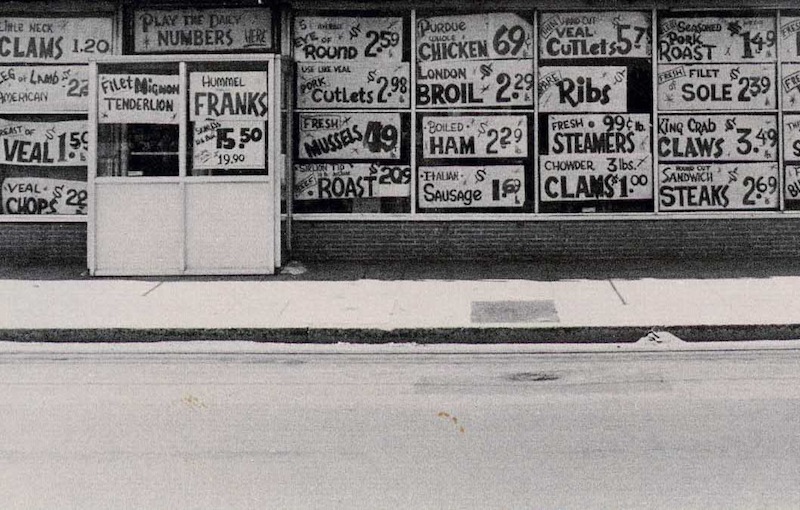

Exposure: Andy’s Food Mart by Tibor Kalman and M&Co

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: License Photo Studio by Walker Evans

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Drape (Cavalcade III) by Eva Stenram

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Mrs. E.N. Todter by Dion & Puett Studio

Related Posts

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Andy’s Food Mart by Tibor Kalman and M&Co

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: License Photo Studio by Walker Evans

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Drape (Cavalcade III) by Eva Stenram

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.