May 3, 2018

The Times. A Comic Strip. A Pulitzer Prize.

It is not every day that a comic strip wins the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning—come to think of it, there’s never been one. Art Spiegelman received “a special citation” in 1992 for his two-volume “commix” memoir Maus, which launched a literary genre called the “graphic novel.” But the operative word is “special.” For decades before and after, the coveted prize has gone to exceptional but traditional editorial page cartoonists, like Jim Morin (Miami Herald), Signe Wilkinson (The Philadelphia Daily News), Ben Sargent (The Austin American Statesman), and other regularly appearing single-frame graphic commentators. Not only did this year’s award go to the New York Times, which for decades has strictly adhered to the policy of not employing staff editorial cartoonists, but it went to a comparatively short-lived strip, “Welcome to the New World,” a long-form visual narrative by freelance writer Jake Halpern and freelance illustrator Michael Sloan. That is news. The Pulitzer citation reads, “For an emotionally powerful series, told in graphic narrative form, that chronicled the daily struggles of a real-life family of refugees and its fear of deportation.”

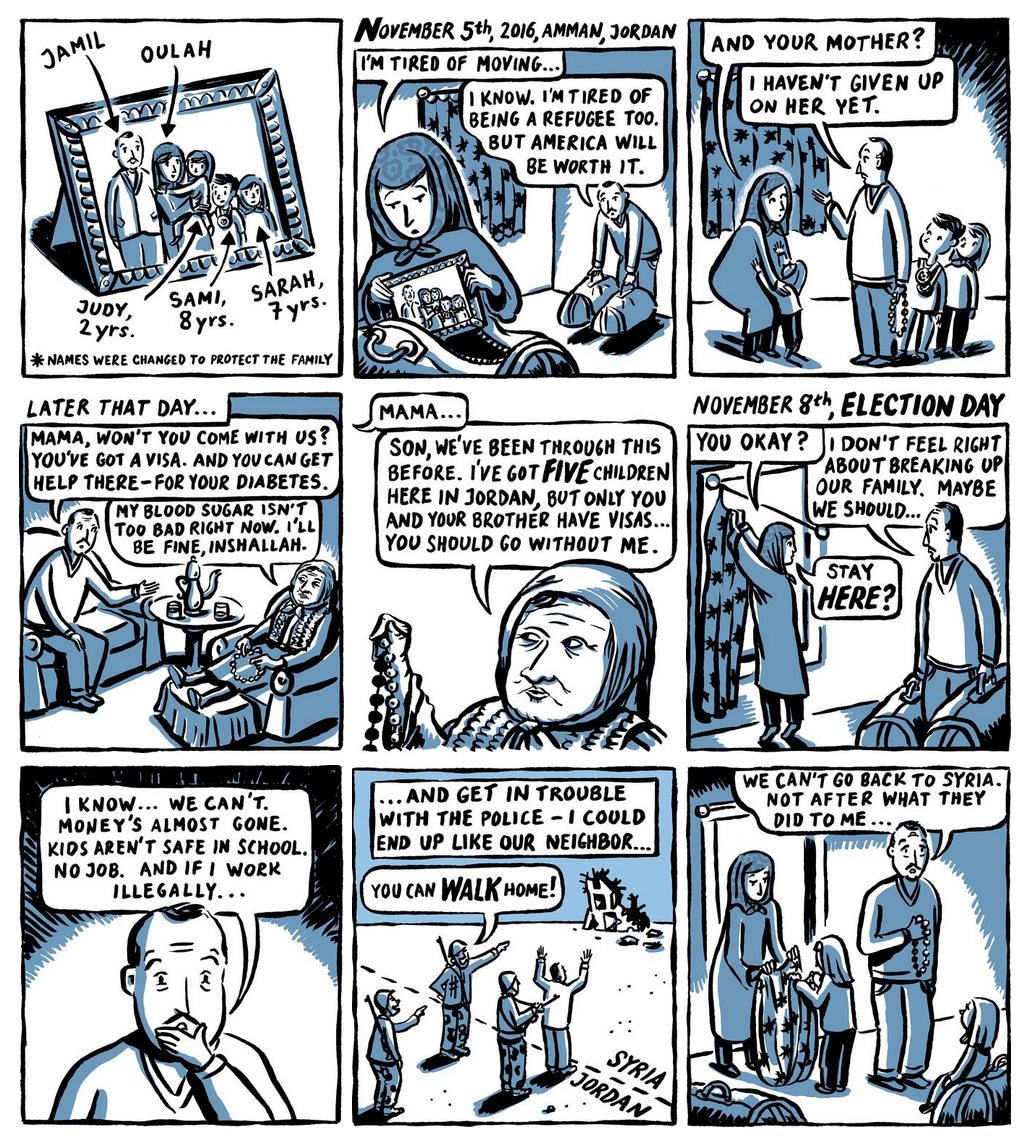

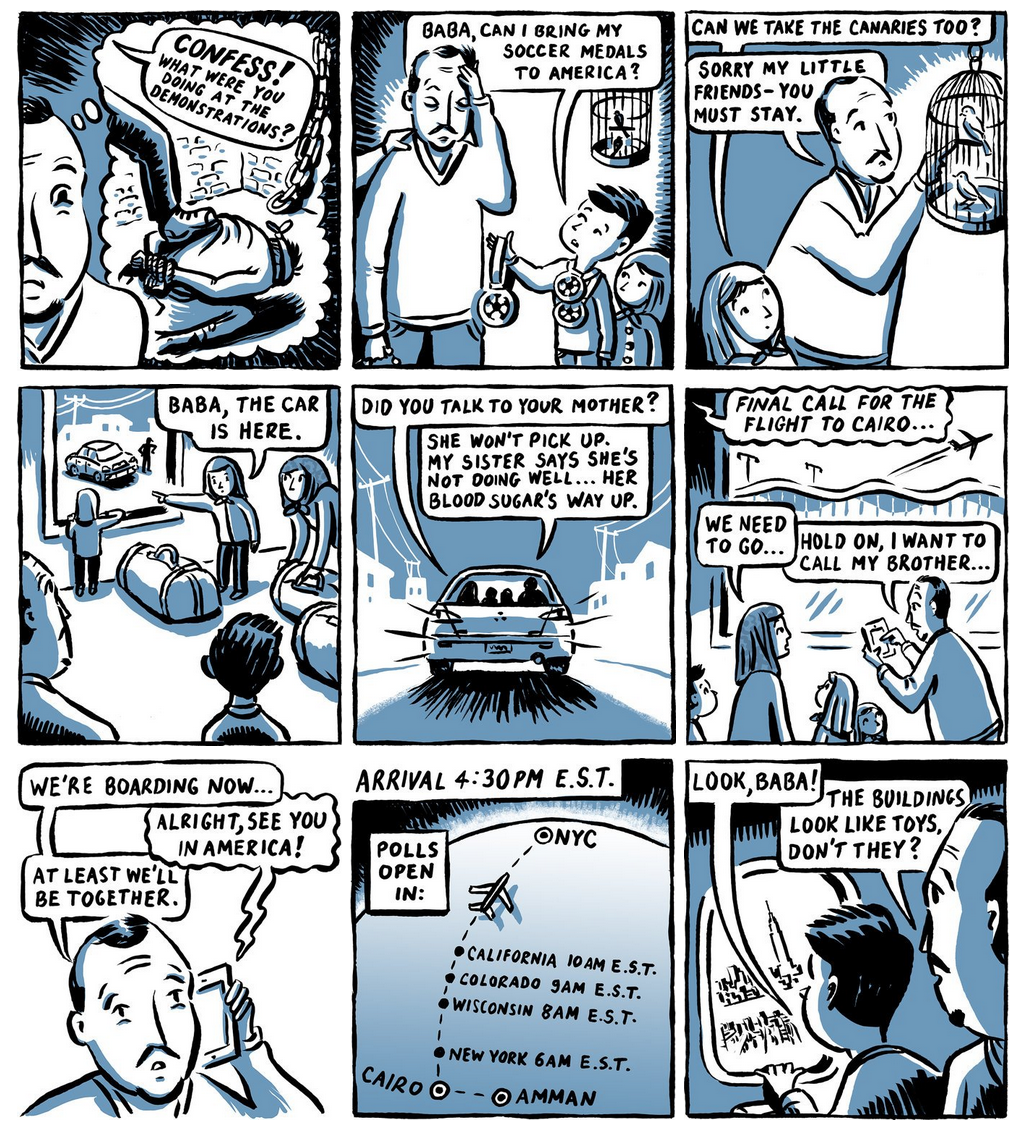

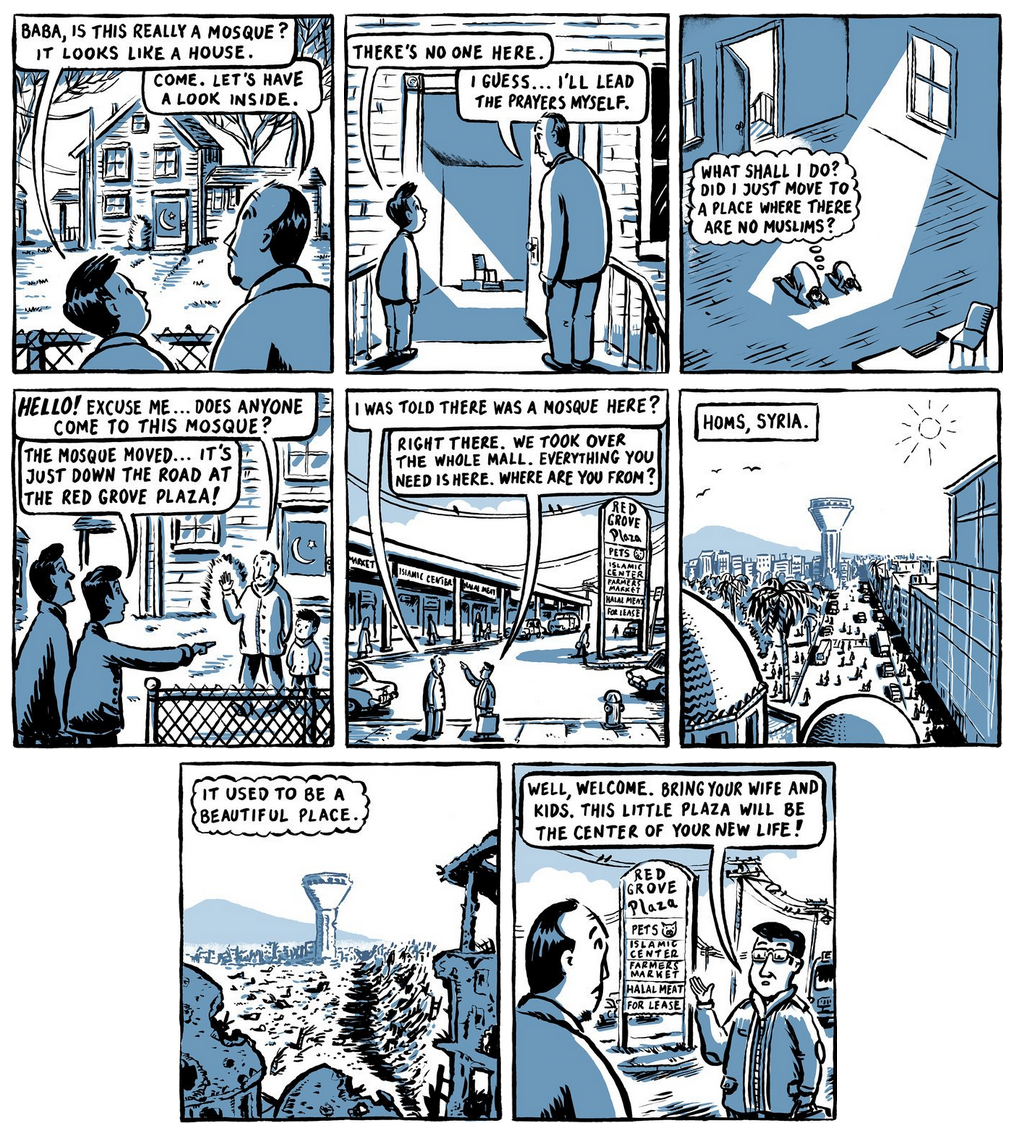

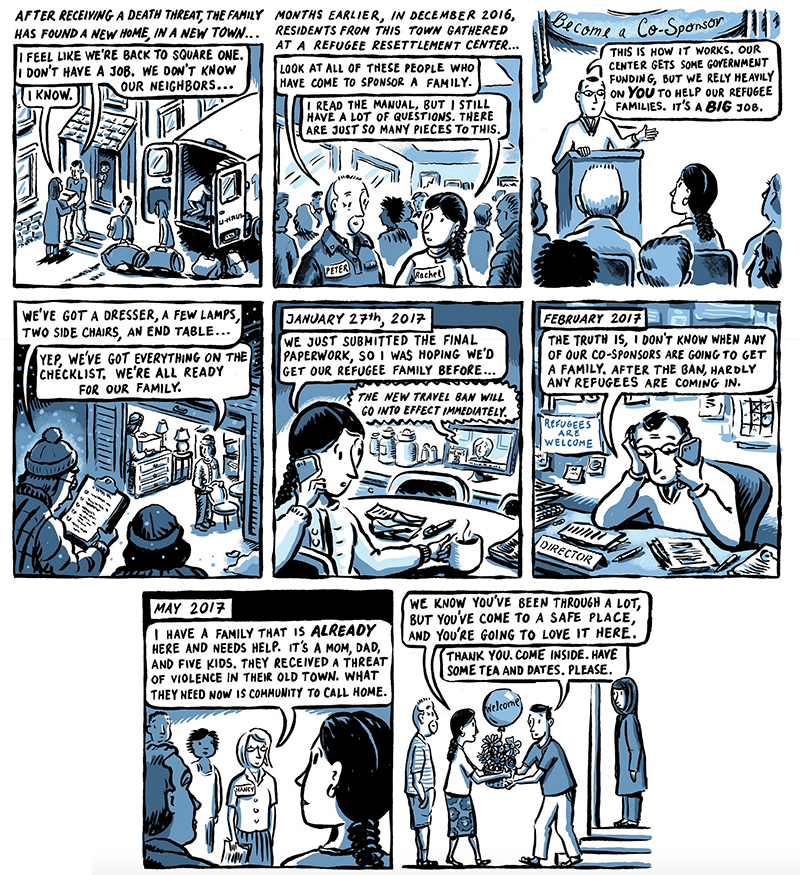

“Welcome to the New Word” follows two families of Syrian victims from the catastrophic civil war. Through its narrative simplicity and unfettered drawing style, the strip provides insight into the trials, courage, and emotional complexities of these uprooted people. Like all solid reporting, the journalism informs and inspires, and the art adds another integral human dimension.

At one time known as “The Old Grey Lady” for its deliberate preference for a high ratio of text to image, the New York Times has for over forty years been a wellspring of many different kinds of graphic reportage, criticism, and illustration. The Pulitzer underscores how editors, once adverse to the importance of visual narrative, have changed their tune. This award underscores the changes in how news and narrative are communicated and consumed in this brave new world.

The idea for the strip began when Bruce Headlam, an editor at the New York Times Sunday Review, and Jake Halpern, a journalist, discussed doing a story about refugees. “It was Bruce, a long-term comic fan, who suggested doing it as a comic strip,” Sloan explains. “Jake agreed, and felt that it would be helpful to have an artist who lived locally. He found out about me through mutual friends.”

Halpern and the Times editors came up with the title. “It’s such a great title,” says Sloan, “And has a double meaning: The family is coming to America, which is one meaning of ‘New World.’” The family fatefully arrives on November 8th, the evening of the presidential election. “[They] wake up next morning to discover that Trump has been elected President, and find that America has suddenly changed overnight—that’s the other meaning of ‘New World.’”

Halpern had been in touch with the director of a local refugee and immigrant services agency. The director knew that he wanted to do a story on the experience of a family that had recently arrived in America. Sloan continues, “One day, the director called Jake to let him know that a family (actually two brothers with their respective families) would be arriving in the coming days, and would he like to come along to observe their arrival? At that point I was in the picture, so I came along too. It was extraordinary, witnessing the families as they arrived in vans at night from the airport in NYC after a long flight from Jordan, exhausted, overwhelmed, and relieved. It was very emotional for me, and I told Jake that I felt like I was witnessing a birth.”

The depth of humanity revealed in this comic format is intense. How Halpern developed his story and Sloan determined what style and shape the characters would take was essential to its success. “I think that the humanity of the story is one of its strongest features,” Sloan notes. “For me, part of it is just simply the kind of person and reporter that Jake is. The families might have been wary of him, and unwilling to allow a stranger into their lives, but they accepted Jake immediately and were willing to allow us to document their lives in detail with a great deal of grace and dignity.” Early in the project, the duo decided with the editors at the Times to use pseudonyms and change the appearance of the family members to protect them. “Everything happened so quickly, there wasn’t much time for me to develop the characters—it happened intuitively,” Sloan relates about the process. “I have an old Disney book on animation techniques, and it shows how to develop characters by creating templates of each character in different poses and from different angles. There was no time for that with this comic.”

The family’s experiences dictated how the story developed. It was reported and illustrated in real time, and what happened to the family week to week was the basis for Halpern’s reporting and the script. A real death threat sequence in the middle of the comic was completely unexpected, a very scary time for the family.

Other challenges were more technical than emotional. For Sloan, “it was the sheer amount of work involved, and meeting the deadlines. Each eight-panel comic took me about 24 hours to create from sketches to final art (the full page, 24-panel comics took three times as long) and it took about that much time for Jake to do his reporting work. So it was a lot of work in a very short amount of time for us, initially every week, and then every other week, for 10 months.”

Of course, living, so to speak, with these people was emotionally charged. Halpern met with them about every week to do the reporting, and then would return after he had drafted his script to check facts. He applied the same rigor to his reporting and fact-checking as he does to all of his journalism. Sloan did not interact as much—about every month or so: “My heart went out to the families as they struggled to adjust to their new lives here, and I felt like it was a challenge to keep some emotional distance in order to properly do my work.”

Some aspects of the family’s difficult transition were not used or never going to be used. Halpern had so much material based on his reporting that inevitably, in the interests of time, space, or story flow, some of the family’s experiences were left out.

The strip was on a six-month contract that ended last June, but the Times extended the series through the end of October. It has since been optioned for a film and more fleshed out graphic novel.

I asked Sloan what he would he want the reader to feel about this work.

“The humanity of this extraordinary family of Syrian refugees, and their story,” he said without hesitation. “The recognition that refugees just want the same thing that everybody else wants: a better, safer life and future for themselves, and for their children.” After a brief pause he added, “And I’d like readers to remember the values that the comic represents to me: compassion, tolerance, and understanding. There can never be enough of that in our world, especially these days.”

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Recent Posts

A Mastercard for Pigs? How Digital Infrastructure is Transforming Farming and Fighting Poverty DB|BD Season 12 Premiere: Designing for the Unknown – The Future of Cities is Climate Adaptive with Michael Eliason About face: ‘A Different Man’ makeup artist Mike Marino on transforming pretty boys and surfacing dualities Designing for the Future: A Conversation with Don Norman (Design As Finale)

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,