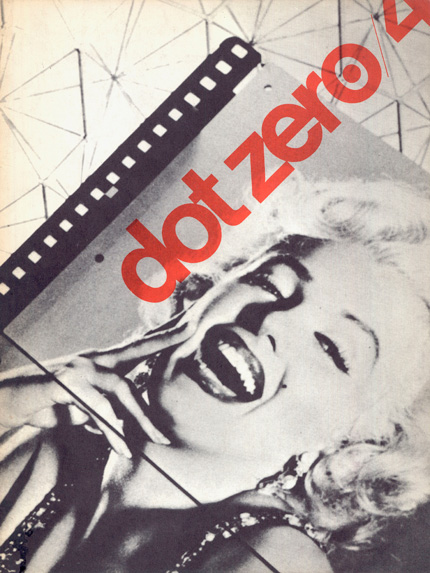

Massimo Vignelli, cover of Dot Zero 4, September 1967

Dot Zero was the house organ of Unimark, the firm that Massimo Vignelli cofounded with Ralph Eckerstrom, Wally Gutches, Larry Klein, Bob Noorda, Jim Fogelman and Bob Moldavsky in 1965. The prototypical corporate design consultancy, Unimark created identities and graphic programs for American Airlines, Memorex, Target, and the New York Subway System that are still in use today. In its attempt to reconcile what was widely considered an intuitive, artistic process with rigorous methodologies and a dedication to sophisticated marketing practices, Unimark in many ways anticipated the current interest in design thinking in business circles, and expanded the debate on the relationship of good design and good business that continues to this day.

In this context, Dot Zero is especially remarkable. Intended as a quarterly, it published only five issues between 1966 and 1968 as a joint promotional venture with paper company Finch, Pryun. In terms of content, it was remarkably ambitious. Its editor, Robert Malone, described its mission in its inaugural issue: "It will deal with the theory and practice of visual communication from varied points of reference, breaking down constantly what used to be thought of as barriers and are now seen to be points of contact." The list of contributors was astonishing for its time, and the topics it covered (new technologies, transportation graphics, semiotics) were not addressed in the mainstream design press then, and indeed in some cases would not be discussed elsewhere in such depth for decades.

Massimo Vignelli was Dot Zero's designer and creative director. Examining the five issues over forty years later, his passion for the project is still evident. Set in two weights of Helvetica (Unimark's signature typeface) and printed on white uncoated paper almost exclusively in black and white, the design of Dot Zero stood out in stark relief to the kinds of self-promotion that dominated the profession in those days, and would be equally distinctive today.

We are pleased to present a slide show of this little-seen publication, along with a short interview with Massimo Vignelli in which he assesses the Dot Zero's legacy.

Michael Bierut:

Do you remember the moment when the idea for Dot Zero came up? Whose idea was it?

Massimo Vignelli:

MB:

Was it a difficult decision to cease publication?

MV:

Massimo Vignelli:

Finch Paper [which is still in business today] was a client for whom we were doing a corporate identity. Ralph Eckerstrom convinced them to sponsor a magazine we had in mind to do as a Unimark house organ. The magazine was presented to them as a vehicle to promote the paper used for the magazine.

MB:

Did Finch know what they were getting into? Dot Zero certainly doesn't look like a paper promotion like the Imagination series that Jim Miho designed for Champion Paper, with lots of demonstrations of fancy printing techniques.

MV:

We did Dot Zero long before all that fancy stuff. That came later. Finch didn't know what to expect. Luckily, the reaction among designers and specifiers was very positive.

Did Finch know what they were getting into? Dot Zero certainly doesn't look like a paper promotion like the Imagination series that Jim Miho designed for Champion Paper, with lots of demonstrations of fancy printing techniques.

MV:

We did Dot Zero long before all that fancy stuff. That came later. Finch didn't know what to expect. Luckily, the reaction among designers and specifiers was very positive.

MB:

How was the content developed?

How was the content developed?

MV:

There was an editorial board consisting of me, Herbert Bayer, Ralph Eckerstrom, Bob Malone, Jay Doblin and Mildred Constantine.

There was an editorial board consisting of me, Herbert Bayer, Ralph Eckerstrom, Bob Malone, Jay Doblin and Mildred Constantine.

MB:

That's a pretty amazing editorial board.

MV:

Yes. And each person would bring different ideas. There was a Aspen connection thanks to Bayer and Eckerstrom. There was a New York MoMA connection with Constantine along with Arthur Drexler. And with Jay Doblin you had the Chicago connection. Bob Malone was mostly operational. His responsibilities were connected with the publishing aspects. We would all meet to discuss the content of every issue. I was designing it, so I participated in all the discussions, suggested subjects, and so forth.

MV:

Yes. And each person would bring different ideas. There was a Aspen connection thanks to Bayer and Eckerstrom. There was a New York MoMA connection with Constantine along with Arthur Drexler. And with Jay Doblin you had the Chicago connection. Bob Malone was mostly operational. His responsibilities were connected with the publishing aspects. We would all meet to discuss the content of every issue. I was designing it, so I participated in all the discussions, suggested subjects, and so forth.

MB:

The first issue featured writing from, among others, Drexler and Marshall McLuhan. Subsequent issues would feature John Kenneth Galbraith and Umberto Eco. How did you get such illustrious writers?

The first issue featured writing from, among others, Drexler and Marshall McLuhan. Subsequent issues would feature John Kenneth Galbraith and Umberto Eco. How did you get such illustrious writers?

MV:

Between the different people on the board, we all knew them personally, more or less, so we just asked them. It was fun for us and fun for them.

MB:

Between the different people on the board, we all knew them personally, more or less, so we just asked them. It was fun for us and fun for them.

MB:

It sounds like part of the purpose was to demonstrate that Unimark moved on a different level than typical commercial design consultants? As if to say, "Other people hire dollar-a-word copywriters; we use Galbraith and Eco."

MV:

That was our class, you got it!

MB:

Did Dot Zero have any models, either from a design, or an editorial point of view?

That was our class, you got it!

MB:

Did Dot Zero have any models, either from a design, or an editorial point of view?

MV:

There was reallly no model, for either of content or design. I wanted to design a magazine with one type size in only two weights, a grid, and one color, just black and white. We wanted something visually exciting, but not visually spectacular. Perhaps one sort of model was Neue Grafik Design, the Swiss magazine from the early sixties. It was also black and white only.

MB:

Did you have complete creative freedom? Were you ever, for instance, urged —or tempted — to escalate to a second color, or full color?

MV:

Never! I was doing the magazine I wanted to have and Ralph liked it! We completely agreed on what we were doing. We were just doing what we wanted to do.

MB:

How was each issue assembled? I assumed it was all put together from galleys originally set in hot type but maybe you were already into photocomposition.

MV:

Never! I was doing the magazine I wanted to have and Ralph liked it! We completely agreed on what we were doing. We were just doing what we wanted to do.

MB:

How was each issue assembled? I assumed it was all put together from galleys originally set in hot type but maybe you were already into photocomposition.

MV:

No, no, no. It was all just cut and paste. I can't believe it now, but that was all we did at that time.

MB:

In the end, what were you hoping to accomplish with Dot Zero?

MV:

MB:

In the end, what were you hoping to accomplish with Dot Zero?

MV:

We wanted to create a voice, for Unimark, and incidentally also one for Finch Paper. We wanted to do things that commercial magazines would not even consider. We wanted to show what kind of company Unimark was. That we were a "high brow" group rather than one oriented only toward profit.

MB:

MB:

In that light, I'm struck by what must have been the contrast between Dot Zero and other design magazines at the time. Did you have any hopesl that the level of design discourse in the US would be elevated? It was an example of design history and criticism in action that wouldn't be repeated for years, basically. Do you remember how the recipients responded to it?

MV:

MV:

Of course elevating design discourse has always been my goal. And designers were in awe of Dot Zero. They had never seen anything like this in the US. There had been beautifully designed magazines in fashion and other fields, but not in our field.

MB:

Did you succeed?

MV:

I think that Dot Zero contributed a lot to positioning Unimark, at the beginning at least, as a superior design company. As long as the sponsor supported us, we were able to continue at that level. Impossible without the support.

Did you succeed?

MV:

MB:

Was it a difficult decision to cease publication?

MV:

Not difficult, but necessary. We couldn't afford paying for it ourselves, and it was not so easy to find another sponsor. I am sure that Ralph may have tried to find other sponsors, but at that time most companies were more interested in direct advertising expenditures than these kind of intellectual exercises.

MB:

In the end, do you think Dot Zero made a difference?

MV:

Yes. And today I see issues for sale on Ebay for $150 and even more!

Comments [3]

09.16.10

01:24

10.31.10

01:41

Is there an online copy of the articles included in this magazine? I'm looking for the ones in Dot Zero 4 in particular.

09.20.11

12:01